If you’ve ever attended a Gawai celebration in Sarawak, you’ll find out quickly enough that no one leaves without at least a generous sampling of home-brewed rice wine.

In Sarawakian Dayak culture, tuak and langkau are part of the social glue that holds communities together.

They’re poured to honour ancestors, welcome strangers, repel malevolent spirits (or bad vibes, in the modern context) and toast to just about everything worth celebrating.

So, what exactly is tuak?

The many different types of modern-day tuak. Photo: Irene Chan.

Tuak is a variety of rice wine commonly brewed by the Iban, Bidayuh, and other Dayak communities in Sarawak, although the Orang Ulu and Penan tribes have their own versions with slightly different fermentation techniques.

Your first sip of tuak might taste oddly familiar. This is because it is essentially the Bornean cousin of Japanese sake or Korean makgeolli, but distinctly local in flavour and intent.

As with its East Asian equivalents, tuak is usually made from glutinous rice, sugar, ragi (natural yeast)—sometimes handed down through generations—and water.

After weeks or months of fermentation, the result is a cloudy, mildly sweet, surprisingly smooth drink that sits around 8–15% alcohol—similar to grape-based wines— depending on how long it is left to mature.

That said, just about anything with some sugar content can be used, and that has spawned a myriad of tuak varieties as diverse as ginger, dragonfruit, pineapple, sugarcane, and even tuak buah tampoi, a sweet-and-sour wild fruit native to Borneo.

You’ll most often see tuak served during Gawai Dayak, the harvest festival celebrated in June. If you visit any longhouse, you’ll find yourself offered a small glass as soon as you step in.

Tuak: The Sarawakian Welcome Drink

Iban men dressed in traditional outfits for the Kuching Parade. Photo: Lynda Lee.

Tuak is deeply tied to festivals like Gawai Dayak, weddings, and even funerals. It forms a considerable part of socialising in the local culture, and it is a beverage that heralds kinship and jovial bonhomie. It’s a drink meant to be consumed with others: the more you drink, the warmer the welcome you receive.

To be clear, the Sarawakian drinking culture is not about getting tipsy, although that can be a… let’s call it a happy side-effect. The true purpose, however, is participation.

When you set foot in someone’s home, the original intent of welcoming drinks is as a ritual to appease the spirits that might plague an otherwise peaceful gathering.

If someone offers you a shot of tuak, especially an elder or host, it’s considered impolite to decline, unless you have a really good reason… Like being unconscious (and I’m not even joking).

Langkau: Tuak’s more potent counterpart

Some of the author’s personal collection of tuak and langkau collection. Photo: Irene Chan

Langkau is a distilled rice liquor: tuak’s bolder, older sibling with enough potency to floor even the most seasoned drinker — the alcohol content could be as high as 40 to 50% ABV. It is very similar to vodka, albeit made from rice instead of potatoes.

The name derives from the Iban word, langkau, which alludes to a home-brewed drink distilled in a small hut, which gives you an idea of how it is traditionally made.

Interestingly, there are similar rice-based white spirits all over the region, with names that even sound similar — in Thailand, they call them lao khao, and in Laos, shots of the ubiquitous lao-lao is added to anything from fruit smoothies to coffee.

And of course, let’s not forget the searingly potent baijiu from China, or the milder versions from Japan (shōchū) and Korea (soju).

Langkau is still very much handcrafted in small batches, usually made in home distilleries that make use of improvised stills cobbled together out of bamboo pipes and pots, with langkau makers drawing upon inherited know-how from previous generations.

While tuak is simply the outcome of fermenting sugars, langkau takes it one step further — the fermented rice mash is heated up, and the evaporated alcohol is collected and cooled back into liquid, now with a higher alcohol content.

Alcohol distillation using traditional means is a tricky process, with the first run being potentially toxic, and the final runs often bitter-tasting and lacking in the smooth quality that is sought after in white spirits. Experienced distillers know how to judge the various cuts by smell, taste, and flow rate without any sophisticated instruments involved.

Langkau is usually sipped slowly, as opposed to being gulped down in quantity, and is often shared among elders or close family in smaller, more private settings.

There are, of course, anecdotes on the medicinal properties of langkau—you’ll hear stories of it being used to treat muscle aches or insomnia. Whether or not that’s true is an entirely different debate.

Booze as Tradition, Respect, and Bonding

One of the older longhouses in Sibu, Sarawak. Photo: Lynda Lee

Tuak and langkau aren’t just home-made moonshine purely for the purpose of consumption. They’re offered as part of the Sarawakian communal culture, and carry hundreds of years’ worth of history and meaning.

When someone pours you a portion of tuak, they’re proffering you their hospitality, friendship, and a piece of their culture.

It’s common during Gawai for people to go ngabang (house-hopping) and be welcomed with food, music, and, of course, tuak.

If you are a particularly honoured guest, your host may even be prompted to crack open the very last bottle of tuak their late grandmother made — just for you. At weddings, VIPs are sometimes offered aged tuak, some as old as a decade, carefully stored for only the most important occasions.

Sometimes, before the first sip is taken, a small amount is poured onto the ground as a libation to honour the ancestors. It isn’t done very often these days, but it’s a reminder of how closely linked these traditions are to spirituality and respect.

And of course, every family has its recipes for its version of rice wine—some sweeter, some drier, some even mildly fizzy, or with a secret ingredient no one outside the family will ever know.

Skilled tuak-makers can make tuak to a given specification by adjusting various factors —for example, different yeast strains can produce very different outcomes.

From Sarawakian Kampungs to Speakeasies

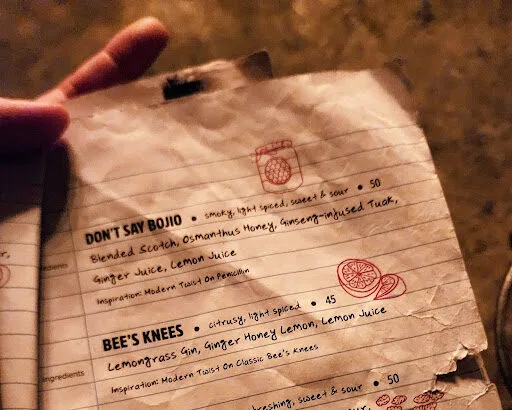

Tuak cocktail on the menu at a speakeasy bar in KL. Photo: Irene Chan.

What used to be a drink found only in Dayak homes, once ridiculed as cheap local moonshine, is now appearing in trendy hidden bars in KL and Borneo-themed pop-ups.

You might see tuak at a Gawai night hosted by East Malaysian student groups, or on a curated menu at a Sarawak-themed bar in TTDI.

Bottled tuak is even being sold at craft markets and online shops, marketed to curious West Malaysians as “Borneo’s artisanal rice wine.”

Some enterprising brewers have started experimenting with a broader variety of flavours— there are now even coffee-infused versions, and a sparkling version touted as the Sarawakian equivalent of champagne!

While slower to gain popularity, flavoured langkau versions now exist, and there is even a Sarawakian gin crafted from langkau.

Both tuak and langkau are clearly catching on with younger Sarawakians and adventurous Peninsular Malaysians alike. On one hand, it’s heartening to see this unique tradition gain more visibility. On the other hand, some worry that turning tuak into just another hipster experience could dilute its roots.

The question is: what is tuak and langkau without the cultural context? Would the experience be the same without the people, the stories, and the shared plastic cups on a longhouse ruai (veranda)?

A Sip of Sarawak: And Why it Matters

Some of the participants of the recent Kuching Parade. Photo: Lynda Lee

Malaysia is a patchwork of diverse cultures. We say this a lot, but often, we limit our understanding to things within our immediate reach, including food, language, customs and attire.

Tuak and langkau are reminders that there’s so much more to what we know about Malaysian culture, especially that of East Malaysia.

They may seem like “just drinks”, but should you ever find yourself in a longhouse, sitting cross-legged, sharing in a round with strangers who suddenly feel like cousins, you might just begin to understand why these beverages are so intertwined with the Sarawakian cultural identity.

I wrote this article in the hopes of clarifying that the rice wine culture in Sarawak is not about mindless inebriation, but rather, about connecting with indigenous communities and showing respect for their traditions.

Whether you’re sipping tuak (“Last year’s batch was especially good!”) at a family gathering or trying langkau for the first time, praying you’ll wake up tomorrow with your memory intact, remember this: you’re tasting a rich and generous culture that is still very much alive.

So, the next time someone from Sarawak offers you tuak, take it. Sip it slowly, and ask where it came from. They’ll appreciate your curiosity and openness to the experience. And you’ll probably gain a story (or two, or three) over cheerfully-poured refills.

Have a story to tell?

Share your story on our Facebook page and you may be featured on In Real Life Malaysia.

I Made Sure My Ex-husband Lost Everything After He Cheated On Me With A 21 Year Old Influencer