Disclaimer: In Real Life is a platform for everyday people to share their experiences and voices. All articles are personal stories and do not necessarily echo In Real Life’s sentiments.

Story by Carmen Tan

“You’re not Chinese. Nobody wants you,” mocked the cruel voice through the toilet door.

“Let me out! Please!” I begged.

“No. Go and flush yourself down the toilet bowl.”

I was in Standard 1. I had been enrolled, against my wishes, in a famous SRJK(C) school in the Klang Valley.

Early on, I had trouble making friends. One day, a group of my girl classmates invited me to go to the school toilet with them.

Bursting with glee at the thought of being friends at last, I followed them… and they trapped me in a cubicle.

I pleaded to be let out, but they refused, hurling insults at me through the shut toilet door. I’m a banana. I’m not Chinese enough. I’m a failure.

Well, they were right about the banana part. And because of this, my classmates took my pocket money.

I speak English as a first language at home. My values are western, and I enjoy western pop culture.

So what? you ask.

So a lot of things, to the teachers in my Chinese school.

For one, I am most comfortable speaking English. Eventually, my class teacher got fed up. So, she decided that any one of my classmates could take all my money if they caught me speaking English.

My classmates would trick me into saying English words so they could pinch my cash, and when I did not fall for it, they would take my money by force.

For years, I lost my daily pocket money like this. I could not tell my parents, as they did not believe me. In fact, they would punish me further for “lying” or “exaggerating”.

Throughout my years in Chinese school, I was never allowed to forget that I am a banana.

Picture credit: The Star

It was firmly embedded in my head that I was different.

My teachers and classmates constantly reminded me that I was less than.

They would tell me that I was a shame to my parents, to my country, to the Chinese race. I would be better off dead. I had no future in life.

As far as I can remember, I was the only banana in my circle. I am sure there were more in my school, I just didn’t get to know them.

However, I do remember this Eurasian girl—half white, half Chinese. She had light brown hair and Caucasian features, and I remember my peers disliking her for it, calling her names.

I do wonder if she received the same type of treatment as me.

I was caned daily.

For speaking English. For failing to achieve desired grades. For making mistakes. For speaking in class. All sorts of things.

Getting canned and screamed at became such a normal part of my day. And since the teacher couldn’t cane me into becoming a ‘better’ student, they sent me from class to class to tell them, “I am a shame to my parents. I am a lazy good-for-nothing. I am a useless girl.”

Eventually, I had to go to the staff office to recite those lines, or to the headmistress’ office.

The other staff would ignore me, but the headmistress caned me once.

Once in Standard 2, I desperately needed to use the bathroom.

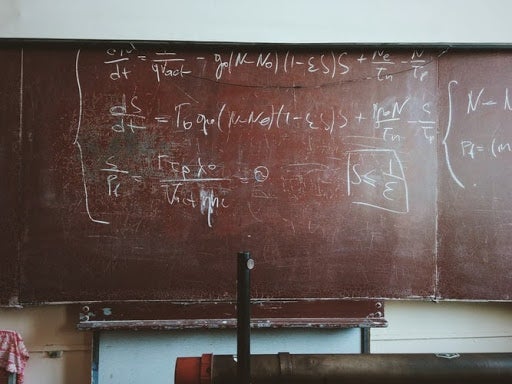

I asked my teacher for permission, but my maths teacher refused. Instead, she forced me to solve an equation on the board first.

When I got it wrong repeatedly, she screamed at me and caned me until I wet myself in front of the whole class.

After that happened, she screamed at me again and caned me some more, then sent me outside to stand under the sun until I dried off.

Up until that point, I was consistently scoring 80 — 100 marks in maths.

But after that incident, I have never been good at maths.

Picture credit: Roman Mager @ Unsplash

My class teacher from Standard 4 to 6 used to impress upon me how useless, worthless, lazy, and stupid I was.

She also got a kick out of telling me to die so that my parents will not have to waste their money raising me.

This was in addition to caning in front of the whole class.

Twice a week after school, I would go to her house for tuition class, during which she would cane me further.

She would burn incense, blare chants from Buddhist sutras while yelling at me as I sat there trying to complete my exercise sheets.

“You’re a disgrace! Repent! Learn some shame!” she would scream. And when I made more mistakes, she would cane me some more.

Once, I corrected her English, and she whisked out her kitchen knife, lecturing me about respecting my elders and teachers.

Picture credit: Nyguyen Khanh Ly @ Unsplash

My English teacher in Standard 5 and 6 was the only reprieve I had.

English class was the only class where I escaped the cane, because I thrived at English.

Of all my teachers, this English teacher’s face has left the most lasting impact on me, because she always looked at me sadly.

In Standard 6, she picked me to join a writing competition.

It was one of the proudest and happiest moments of my young life!

Actually, my poor performance was because English is my first language and I had trouble understanding the lessons in Chinese.

When I enrolled, I could not string together a single sentence in Mandarin.

Naturally, this caused plenty of stress. Coupled with all the verbal and physical abuse, it was no wonder I couldn’t score As.

However, I miraculously scored straight As in UPSR.

Today, I am an academic. I hold a master’s degree.

I also know 5 languages and 4 dialects, proving that I am actually good with languages.

I only wish that I could experience Chinese—both the language and culture—in a gentler environment.

Picture credit: Thought Catalog @ Unsplash

Both my parents were English-educated.

Hence, they could not help me with any of my school work.

However, they wanted my sibling and I to “go back to our roots”.

They also figured that learning an extra language won’t hurt, as mastering Mandarin would mean more opportunities.

As such, we were forced through the SRJK (C) system.

I did not have a say in this.

Around Standard 3, I begged to be sent to a different school, but my mum convinced me that changing school would mean losing all my friends and never making new ones.

I was determined not to lose my single close friend at the time, so I obliged and stayed on.

But who am I kidding? Leaving wasn’t really an option.

And hence continued the saga.

I am still processing the trauma today.

Those six years in Chinese school cemented that I will never be Chinese enough. As a result, I leaned hard into the English language.

Up till today, I have never touched any Chinese media or Chinese pop culture.

I simply don’t want anything to do with the Chinese culture anymore.

Maybe many many years in the future, I would unlearn my hate and bitterness, and approach the Chinese culture again.

Maybe.

Picture credit: PTMP @ Unsplash

My takeaway from my Chinese school experience is that a lot of Chinese people grow up in social bubbles.

Quite often, their world views are narrow, fixed on one ‘best’ way to get things done.

Throughout my six years there, the teachers and students knew only one means to education: rote memorization, straight-A results, and using physical pain to shame and push the children into “success”.

Not to forget all the propaganda: Calls to always remember your alma mater—the SRJK(C) school, likened to a firm but loving mother. Be grateful to her. Support her financially. Chinese people are a superior race, as evidenced by our grades.

Not to forget that Malaysian Chinese tend to have a victim complex, and this was drilled into us in Chinese school: The government and other races do not like us Chinese, and they are all against Chinese education.

The solution is that Chinese schools need to fund themselves, and thus the students are exploited, going door-to-door, bugging every relative and friend, begging for donations.

Failing to collect a certain amount of donations earned me more caning. I failed every single time.

No doubt there is beauty in Chinese culture, but they are only available to the insiders, not an outsider like me.

Differences were not tolerated. Maybe my experience was unique, and it is possible to have a perfectly enjoyable SRJK(C) experience as a banana, but that was not what happened to me.

Until today, I feel like a stranger in my own home. The government labels me a “pendatang,” whereas my teachers and peers in school, as well as my Chinese-educated relatives full-on rejected me for being “not Chinese enough”.

Sometimes, I look at Chinese culture and feel like a tourist.

Sometimes, I watch documentaries about what is supposed to be my own culture and wonder what it would feel like to have a sense of belonging and pride in family history and cultural roots.

Picture credit: Zhang Kaiyv @ Unsplash

The 2008 Beijing Olympics was probably the first time I felt proud to be Chinese.

I saw people who looked like me achieve great feats in an international arena.

Nevertheless, it was a distant feeling. It was a far-fetched identity I could not claim.

Since then, I’ve visited China a few times, but I feel no connection to my ancestral motherland.

It’s been 4 generations since my ancestors left China, so that is not my home. Malaysia is.

In my work, I sometimes encounter archival text on early Malayan Chinese.

While I’ve read some terrible accounts proving that classism was rampant even back then, sometimes religion succeeds in binding people together, like the Feast of St. Anne’s at St. Anne’s church in Bukit Mertajam.

The feast of St. Anne is an annual event that spans 10 days and usually attracts thousands of pilgrims from all over the world.

Every year, people of diverse races, ethnicities, and language unite to celebrate. Those are interesting intersections of unity to me.

Language greatly divides Chinese-educated and English-educated Malaysian Chinese.

Of course, each has its benefits. As a banana, I have greater, earlier, and far easier access to a larger Western pool of academic resources.

Naturally, my perspectives will differ from Chinese-educated folks who have access to a completely different pool of resources and maybe only encounter new perspectives at the university level.

Nonetheless, I observe that because of these differing vantage points, there is conflict between Malaysian Chinese across the language divide.

For example, Chinese-educated individuals tend to have Confucian values ingrained in them, which are collectivist in nature. Everybody has a role to play, which is also why gender roles are a norm in traditional Chinese households. The role of the children is to serve their elders, even if this means sacrificing their own sense of self, dreams, and ambitions.

On the other hand, bananas are more individualistic. That’s why non-conforming bananas usually have an easier time than their Chinese-ed counterparts.

In other words, to the Chinese-ed, the family is the smallest unit, whereas the bananas view the individual as the smallest unit.

This would subconsciously affect one’s attitude about money, career, life partner, etc.

I sincerely hope that SRJK(C) schools are different now.

I think more students would have thrived and lived far healthier childhoods if schools could accept “being different” as new learning opportunities, rather than punishing children for being who they are.

Being a banana is who I am now, and who I was as a kid. Just because I speak English, enjoy western pop culture, or hold values associated with the west does not make me a failure in life.

It does not mean that I have failed my parents, my ancestors, nor my country.

I just wish my teachers knew that.

For more stories like this, read: How I Survived in the Working World without Reading or Writing Mandarin and What’s the difference between SJK(C) and SK Schools?

To get new stories from IRL, follow us on Facebook & Instagram.

You might also like

More from Real People

“I only wanted to help him stand up again” Elderly Man’s Kind Gesture Ends in Debt and Gambling Fallout

A well-intentioned act of kindness quickly turned into a heartbreaking lesson about the dangers of debt and online gambling after …

“I Was In Tears” shares Activist who Rescued Elderly Man From Run-down House

This story is about a Malaysian activist who rescued an elderly man allegedly locked inside a dilapidated home in Kelantan …

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …