This exclusive story is brought to you by In Real Life Malaysia – For sharing, please credit us and add a backlink. We value your kind acknowledgement of our editors in sourcing and conducting interviews.

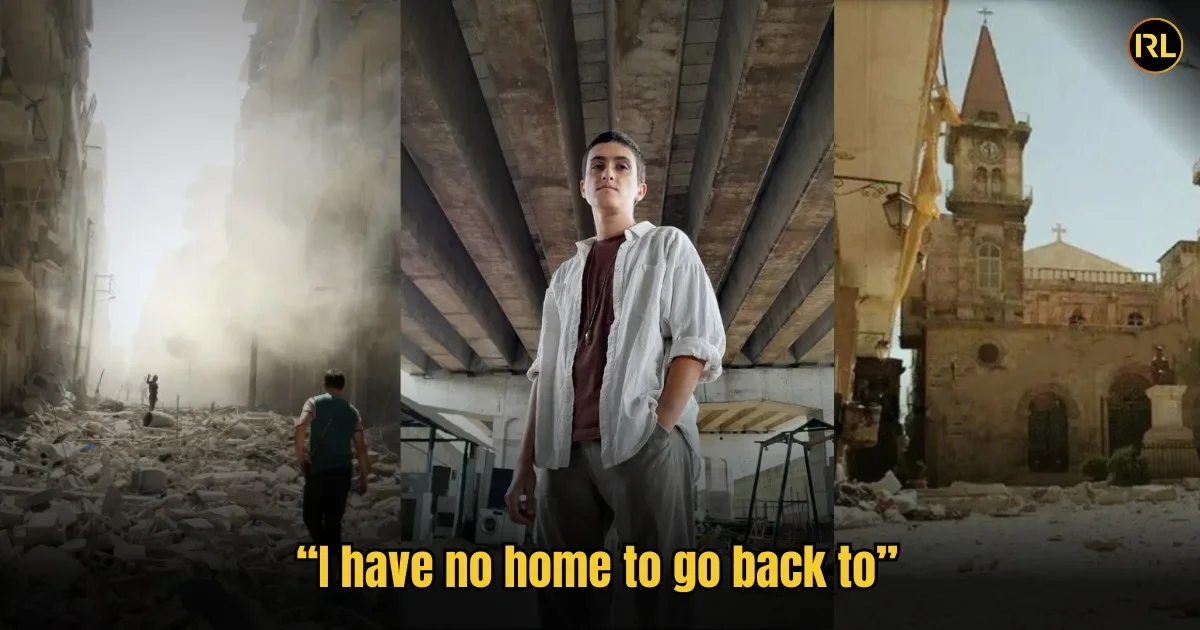

This story is by Amar from Syria who shares what life is like as a refugee in Malaysia and the stereotypes that come with it.

I still remember the first time someone told me, “Oh, you don’t look like a refugee.” It was meant as a compliment, but it stung. What was I supposed to look like? Unkempt, defeated, hopeless? Did people expect me to fit into some box that made them feel more comfortable about my story?

I am Amar, a refugee from Syria. Back home, I was an English Literature student, writing stories about hope and resilience. My family wasn’t just educated; they were passionate about learning. My father was a professor, and my mother, a school principal. We lived a comfortable life—until the war turned everything upside down.

I chose to hide instead of risking my life on a lifeboat

When the war in Syria broke out in 2011, my city was attacked. Many of my friends and family took a very dangerous route to get to Europe. You had to cross the border into Turkey, and then take a ferry or lifeboats to Greece across the sea and further out to Italy, Spain, or France.

Those lifeboats were death traps for people like me. For a lifeboat with a capacity of 50, they would take 200-300 people. You had no choice where you would end up – if you’re not lucky, the authorities would catch you and send you back to Turkey. A lot of people drowned on those boats.

Since I didn’t want to risk losing my life, I hid and waited for the war to end. But after 8 years of constant fighting, I saved what little I had and booked a flight to the nearest country that didn’t require a visa on entry – Malaysia.

How I survived in Malaysia without the right to work

Image credit: gabriel g.

The first thing you learn in Malaysia as a refugee is that “work” is a dirty word. Officially, we aren’t allowed to work—not even part-time. Still, people find ways to survive.

For me, I ended up in the F&B industry. It’s all under the table, without an employment contract, and we get paid in cash. Employers like these want to avoid paying EPF and SOCSO for local hires, so they will hire refugees, because we won’t ask for those benefits that are given freely to Malaysians.

The pay is RM1,700 to RM1,800 a month for a grueling schedule: 12-hour shifts, six days a week. That’s 72 hours of work per week for a paycheck that barely covers rent and food.

But what choice do we have? For nearly three years, I worked in cafes, restaurants, even fine dining establishments. The work was exhausting, but at least it was something—something to keep my hands busy and my thoughts from wandering back to what I’d lost.

We had to abandon our dreams along the way

I met another Syrian man during one of my shifts. He worked in F&B too, but his story broke my heart. Back in Syria, he was studying how to make dentistry materials. He had a future, a path laid out for him in a respected field where he could’ve earned a good living.

But here, no dentist would take him. His skills, his education—none of it mattered anymore. Like so many refugees, he had to give up on his industry and settle for whatever work he could find.

Every day in Malaysia feels like walking a tightrope. We’re not allowed to fall, but we’re given no safety net to catch us if we do. Still, we walk. Because what else is there to do?

“You rely on donations from Malaysians”

Image credit: gabriel g.

Once, someone approached me for donations, assuming I was in a position to give. I found it ironic that I was asked to donate for a cause which I didn’t receive any benefits from.

I told them, “I’m a refugee, yet for the last 3 years I’ve been in Malaysia, I didn’t receive any donations from UNHCR. Where are these donations you speak of?”

They looked confused—but they were just volunteers, unaware of how little actually reaches us.

The truth is, the UNHCR gave me a refugee status card, and that was it. With this card, I can technically ask the UN to send me a lawyer if I need one, but even that takes 15 days. Beyond that, we’re left to fend for ourselves. Getting jobs, finding housing—these are battles we fight on our own.

The Malaysian government seems indifferent, relying on NGOs to handle us and move us along. And yet, people here still think we’re taken care of, as if a refugee card is some kind of golden ticket.

“You’re a refugee, but your English is so good”

One thing I had to understand very quickly was that many people in Malaysia have preconceived ideas about refugees. They assume we were uneducated, poor, and desperate.

It was frustrating because I had met so many refugees who were doctors, engineers, and teachers back in their home countries. They didn’t lose their intelligence or skills just because they lost their homes.

One day, I went on a date with someone. During our very interesting conversation he decided to say: “But you speak English so well! How is that possible?”

I smiled and replied, “Because I went to uni I guess, just like you. Refugees don’t all come from the same circumstances. Many of us were professionals, students, and artists before conflict uprooted us.”

Another time, I overheard someone whisper, “She doesn’t look like a refugee.” I couldn’t hold back. “What does a refugee look like to you?” I asked. They hesitated, mumbling something about poverty and despair.

I took a deep breath and explained, “We are individuals, each with our own stories, struggles, and strengths. Some of us had to leave everything behind, but we didn’t leave behind our minds, talents, or humanity.”

These stereotypes about refugees are dangerous

Image credit: gabriel g.

I’ve seen how dangerous these stereotypes can be. They strip us of our individuality and reduce us to a single narrative of victimhood. But I’ve also seen how stories—real, diverse, human stories—can change perceptions.

Refugees are not a monolith. We are people, each carrying our own dreams, skills, and aspirations. Some of us hold degrees, others carry the weight of experiences you could never imagine. But what we all share is the desire to be seen as human, not as a stereotype.

So, the next time you meet a refugee, resist the urge to assume. Ask about their story instead. You might be surprised by what you hear.

Amar is an art teacher and artist from Syria. If you would like to support them financially, you can follow their Instagram:

Have a personal life experience to share?

Submit your story and be heard.

Email us at ym.efillaerni@olleh and you may be featured on In Real Life Malaysia.

Also read: I Earn RM15,000 Monthly as a Designer After Teachers Said I’d Have No Future

I Earn RM15,000 Monthly as a Designer After Teachers Said I’d Have No Future

More from Real People

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …

‘I quiet-quit, upskilled, and tripled my salary,’ shares M’sian engineer

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that loyalty without leverage leads nowhere in the corporate world.After years of …

‘I did everything right, and it still wasn’t enough’ shares M’sian graduate

This story is about a Malaysian graduate navigating big dreams in a job market where a degree no longer guarantees …