Growing up in Malaysia, we were faced with binary choices: RON 95 or RON97. Spicy and non-spicy. Science stream or Arts stream.

In primary school, it was either Sekolah Kebangsaan (SK) or Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan Cina/Tamil (SJK(C)/SJK(T)).

Recently, the government has launched a probe into an SJK(C) school to find out why they are singing the Negaraku in Chinese.

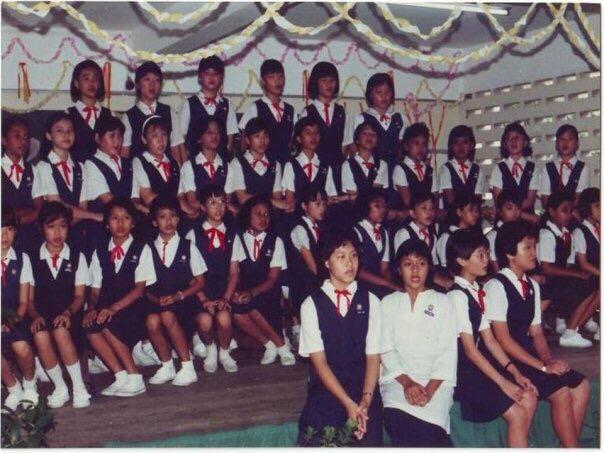

[students singing during recital. Source: aimee thiob]

This has sparked debate once more on the existence of SJK(C) schools and whether they go against the Constitution.

And yet, how different are SJK(C) schools compared to SK schools?

SK and SJK(C) schools: Differences?

For both SK and SJK(C), the curriculum is set by the government. The only real difference is the language for all subjects: Malay for SK and Chinese for SJK(C).

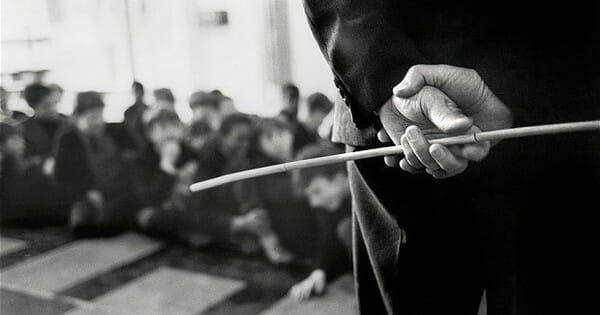

In SJK(C) schools, all teachers would use the cane as punishment.

“We used to hold rankings in class about which teacher had the hardest rotan swing.” said Daniel.

Teachers in SK schools, however, were known for being more lenient.

“In my SK school, only the strict teachers caned. They were the ones that had a reputation. We’d stand up a little straighter when they passed us in the corridors,” Ariff shared.

[source: says]

“The other teachers only verbally chided us, or left us to our own devices,” he said.

Carol went to a SRJK(C) primary school. Funding played a big role in whether a school was deemed excellent or ‘rough’.

“Our school facilities were mostly parent-funded. With each year of donations, they built more and more buildings. We even had aircon for some of our classrooms,” she reminisced.

As a result, SJK(C) schools were seen as ‘effective’ when it comes to academic results. There were even classes for those who were left behind in terms of their grades.

There were also differences in emphasis placed on co-curricular activities. Daniel’s SRJK(C) school, Kuo Kuang was famous state-wide for its basketball team.

“There’s a stereotype that the Chinese kids play basketball, whereas the Malays played football. Me, I preferred to read a book,” Ariff mused.

In SK schools, debate teams in English and Malay were well-known, and conversations about their rankings would dominate the school halls.

SJK(C) Pros and Cons

“I have Malay friends that enrolled their children in SJK(C) schools, because they wanted to give their children the advantage of knowing a third language,’ said Ain.

She also asked her Chinese friends why they opted to put their children in SJK(C).

“They were concerned their children would not be able to speak and write in Mandarin like them,” she said.

For some Chinese parents, it is a mix of pragmatism and cultural heritage that motivates them to opt for SJK(C) schools.

“My dad grew up among Malay peers. When it came to my time, he sent me to a Chinese school to make sure I remembered my Chinese roots,” remarked Daniel.

Daniel’s dad would always remind him that he would be glad he took Chinese when he was an adult, even if he hated it as a child.

“I regret not putting more effort into it now, especially when people who are bilingual in English and Chinese are in high demand,’ he laughed wryly.

There were also downsides to studying in SJK(C). “There’s a stereotype that kids from Chinese schools have a poorer grasp of English,” said Carol.

Chinese-speaking students like Kevin feel that his SJK(C) education taught him how to be good at mathematics, but in the pursuit of academic excellence, neglected his artistic talents.

“When you’re focused on memorization and rote learning, subjects that defy standardised testing (like art) tend to fall to the wayside,” he observed.

[source: malay mail]

SK Pros and Cons

In contrast, the more free-and-easy style of SK schools, with a focus on just keeping kids out of trouble, led to students mingling and playing more easily.

For Clement, he was given a choice to go to SK or SRJK (C) when he was young.

“Knowing the load of homework and stress in Chinese schools, I chose SK,” he grinned. Clement says he enjoyed his time in his SK.

“I speak Malay with a Malay accent!” He chuckled. “People would always ask me if I was Malay.”

He says he’s always related to his Malay friends more than some really “cina” Chinese.

“I don’t always like the very Chinese people – the ah bengs and ah lians,” Clement said.

Ain went to St. Mary’s Secondary School back in 1990. Schools in the 90s, she said, still mixed races. She enjoyed friendships without any racial divides.

“In fact, my 3 BFFs were Chinese. We represented our school at inter-school quiz competitions all over the place, and we would have sleepovers to prepare for the quizzes,” she remembered fondly.

To this day, Ain still keeps in touch with her Chinese BFFs.

Catherine works as a teacher for an SK. She says that teachers are bogged down with administrative work, which cuts into the time needed to spend planning quality lessons.

“We don’t have the time, so we just give students worksheets to do. I feel terrible, but what can you do?” Catherine sighed.

“It doesn’t help that whenever we have a problematic teacher, they just transfer him or her to another school,” she groused.

Without actual consequences for poor performance, teaching quality deteriorates. And so the cycle continues.

[source: berita harian]

Should SJK(C)/(T)s be abolished?

There is a growing sentiment amongst some Malaysians that vernacular schools are an impediment to national unity.

“We must have national education that crosses the barriers of race, religion and ethnicity,” then-deputy PM Ahmad Zahid Hamidi said in an interview with Berita Harian in 2015.

The history of the divide in school language mediums can be traced back to pre-Independence Malaya.

When we were still under British rule, we were segregated by race to keep us from rising against our colonial masters.

This policy trickled down to our education system as well. The British allowed each race to set up their own schools according to their preference.

When we achieved Independence, the schools were allowed to remain, as long as the syllabus was set by the government, and English and BM be compulsory languages taught to foster a common national language, a lingua franca.

To this day, vernacular schools continue to exist.

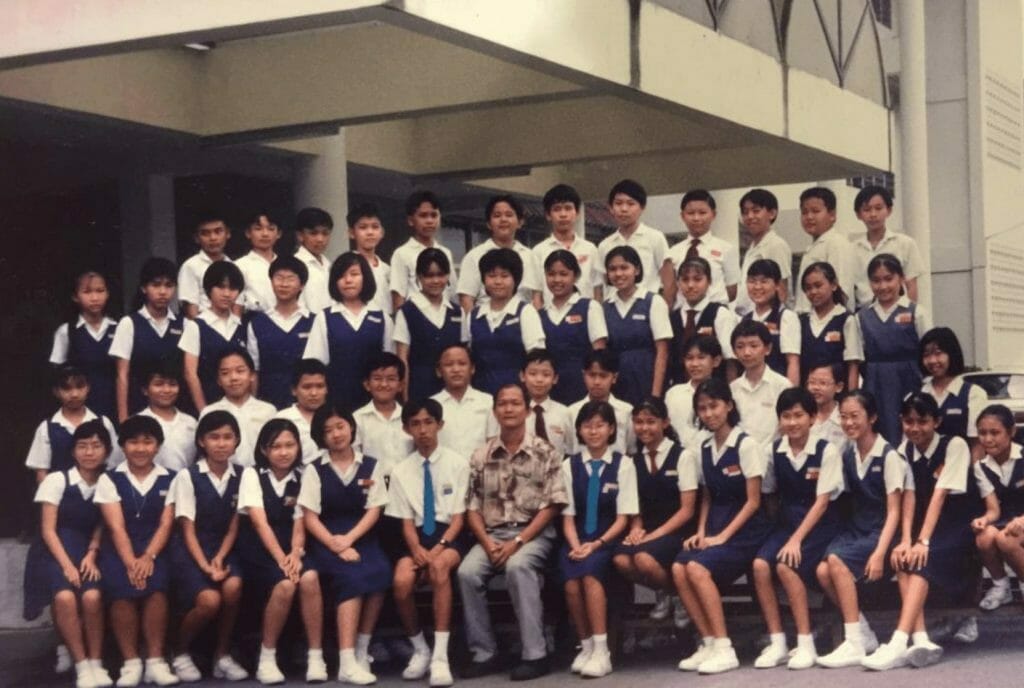

[vernacular schools in the 90s. Source: aimee thiob]

Anyone can learn to be multicultural

At the end of the day, our Malaysian society is made up of people who have gone through both SJK(C)/(T) and SK.

And so far, there hasn’t been much problem communicating because everyone uses either Malay or English in business communication.

The compulsory requirement for BM and English to be taught in SJK(C)s has led to that.

“Even if you streamline every school into government school, will it change anything? Or is this a way to eradicate the culture of the non-Malays?” questioned David, a lawyer and human rights activist.

“Anyone can learn to be multicultural. Schools should instead focus on developing children as human beings, and put less pressure on academic results,’ Carol pointed out.

What do you think about SJK(C) schools? Should they stay or should they go?

Let us know in the comments!

For more articles about the Malaysian schooling system, read Should You Study in Co-Ed or All Girls/All Boys Schools? Here’s What Malaysians Think and I Studied Jawi in School — Here’s My Experience.

You might also like

More from Real People

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …

‘I quiet-quit, upskilled, and tripled my salary,’ shares M’sian engineer

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that loyalty without leverage leads nowhere in the corporate world.After years of …

‘I did everything right, and it still wasn’t enough’ shares M’sian graduate

This story is about a Malaysian graduate navigating big dreams in a job market where a degree no longer guarantees …