“Here, money talks,” Nizam (not his real name), says to me in a WhatsApp voice-recording. “The guy next to me has a handphone. Everybody has a handphone. The officers here don’t give a fuck!”

That was Nizam’s answer when I asked him, “How do you have a handphone in prison?”

At 40, Nizam is currently serving an 11-year prison sentence, for trafficking 5 grams of crystal methamphetamine to Indonesia last year. Despite hiding the drugs in his rectum, Indonesian authorities arrested him on arrival.

The inside of nizam’s cell, measuring 2. 6 x 7. 7 meters, shared by 9 people.

The official story is, the drugs were Nizam’s personal stash and he brought them with him for his own consumption.

At least, that’s what the news portals reported. Nizam tells IRL a different story.

Before his arrest, Nizam was a well-known figure in Malaysia. His late mother had been a popular actress in the 80s, and Nizam followed in her footsteps. He too began a career in acting, and even won an award for local TV.

Despite his bright prospects, there was one thing which was to haunt him throughout his adult life – drugs.

His foray into narcotics started when he first stole his father’s cigarette at 10 years old. From there, he graduated to weed and alcohol at 17, before upgrading to heavy drugs as an actor who loved the partying scene.

“I like to be stimulated,” he tells me.

Had nothing else happened, Nizam would have probably led a relatively normal life, just another young man with a penchant for experimenting with narcotics (not unlike many of Malaysia’s elite actors and actresses). But in 2005, his family received news that would change their lives forever – his beloved mother had cancer.

“She said she found out that the lump in her breast was cancer. Masa tu dah third stage. Even then we knew – this was going to cost a shitload of money.

“I was thinking, how do I pay? How do I help? Everyone else said, ada jalan lain. What fucking jalan you talking about dude? Ini bukan demam, ini fucking cancer!” he exclaims angrily.

To help with the medical bills, Nizam turned to meth, the drug he considered to be most profitable. He wanted to be a pusher at first, but the price of meth was cheap back then, and it wasn’t enough just to sell it.

So Nizam decided to manufacture it instead.

“I went into it. I did my research online for about six months, and then spent another six months learning from trial and error. By the end of 2007, I was a manufacturer of meth.”

Eventually Nizam did make enough money to chip in for his mother’s treatment. He tells me how difficult it was, giving her money he made from the drug trade.

“Yeah, I’m known as the ‘bad boy’ of the Malaysian film industry. But I was brought up by a beautiful, good-hearted woman. Some of it rubbed off on me.

“Every time I gave her money for her treatment, I had to tell her,

“Ma, duit ni, mama bayar bills eh? Bayar bill doctor ker, jangan beli ubat untuk makan. (Mom, use this money to pay the bills yeah? Maybe pay for the doctor’s bills, but don’t use it to buy medicine you’d eat.)

“She would ask me, ‘Nizam, what are you doing? Where is this money from?’ And I’d make an excuse and quickly leave the house. I just didn’t know what to tell her.”

His voice cracks over the recording.

Despite trying to keep his activity a secret, Nizam’s mother would eventually discover the truth. In 2010, Nizam was busted – the authorities found his drug lab.

Surprisingly, Nizam got off, at least for a while. His lawyers argued for and secured him bail, which meant he was a free man until his trial in 2013, where he was acquitted of all charges. The victory was bittersweet – it was also the year his mother succumbed to cancer.

Despite his acquittal, his reputation went down the drain.

“My name was totally destroyed. Totally.” he says.

He was right. Nizam became the ‘black sheep’ of the film industry. He developed a reputation for drugs, which implicated him in two other cases several years later. Eventually, it was also to be his ultimate downfall.

He insists he was innocent for some of them.

“Half of it, it’s not my case. But just because I was in it, suddenly it becomes my case. The drugs weren’t even on me!”

For the next few years, Nizam was in and out of court. He was remanded in 2015, where he stayed for a year before he was acquitted of all charges, again.

When he was finally free in 2016, he was homeless. He had no money, and no place to stay. He ended up squatting at a friend’s place, which was empty and was being put up for sale. He remembers the overgrown weeds and sleeping on the bare floor.

Still, he vowed to turn over a new leaf.

He tried looking for jobs but had trouble keeping one. At one point, he was even a cook at a restaurant. The gig lasted three days. On the third day, his boss pulled him aside and told him, “Dude, sorry ah, my partners, they’re not comfortable with you working here. Takut orang tengok kau kat sini (we don’t want anyone to see you here). Sorry man, gotta let you go.”

Nizam recalls, “We had this conversation over a joint, me and the co-owner. The fucker was on drugs too!”

Eventually, Nizam got a break. Picking up where he left off, he tried going back into acting. He auditioned for a role in a local film. The producers loved him and wanted to cast him as the main antagonist. He was elated.

“I even asked my friends to please, tell the cops to get off my back. Aku dah cuci tangan dah (I washed my hands clean of this). I knew if I did this film, I’ll get back up there. I can pave my way through. All I needed was a shot.”

Unfortunately, his chance never came.

The film production kept getting pushed back, and Nizam wasn’t getting paid. Homeless and broke, Nizam grew desperate. Eventually, he went back to the drug trade.

He got in touch with one of his acquaintances from before, looking for work. His acquaintance, Faiz (not his real name), told him yes – he had a job for him.

“He told me, the job was to go to Indonesia and bring a sample. Show the client (the sample), and if the client is satisfied, bring the client to a Western Union branch, make payment, and the drugs will be sent.”

So Nizam packed the drugs Faiz gave him, stuffed it up his rectum, and boarded a flight to Indonesia.

“When I got off the plane, I was first stopped at immigration for not having a return ticket. I had to bribe my way through, but I made it to customs.

“However, at customs, there were many officers there. It was unusual. That’s when I had a bad feeling.

“Contrary to what they always say, it wasn’t that I “looked suspicious”. They only checked me briefly, but there was already a car prepared to bring me to the X-ray scanner.

“True enough, during my hearing, they admitted that information had been sent over from Kuala Lumpur. They knew my details, my flight number, my seat number, where I hid the drugs – everything.”

Only two people knew about the drugs – Nizam and Faiz. As it turns out, Faiz had betrayed him to set a deal with the Malaysian authorities.

Holy shit. What happened next? I asked Nizam.

Nizam chuckled. “I’m going to send you something, hang on.”

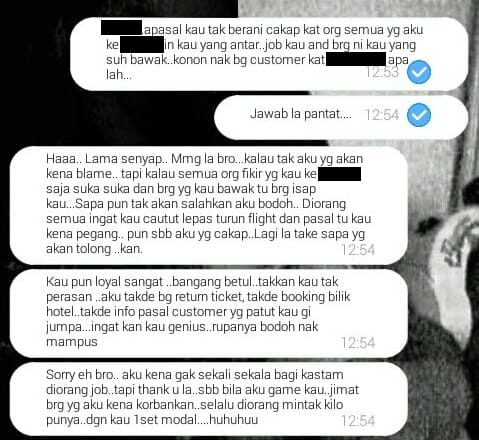

Conversation between nizam and faiz, faiz admitting to him being set-up.

“I was the scapegoat. He saved a lot of money with that bust. When he used me, he didn’t have to plant a lot of drugs.”

Nizam tells me that for busts like these, the minimum is usually 1 kilogram of drugs. Because of his reputation however, 5 grams was enough.

“Usually, who the fuck would want to hear about a foreigner carrying 5 grams of drugs? Unless that foreigner was someone who had a name.

“So yeah – I was set-up by a friend, who knew I had a son back home. (He) knew I was squatting here and there. Basically, he thought, yeah, broken family, no house, nothing, so who’s going to give a flying fuck about me?”

Why not show the messages and say you were being set up?

“The statement I gave was that this was all for personal consumption. Because if I told the truth, I’d be facing a much longer sentence.”

So, what’s next for you? What happens now?

“So, I’ve got another 10 years remaining in my sentence. 11 years for 5 grams is crap. Tapi takperlah, nak buat macam mana kan? (It’s okay, what can I do about it?) I mean, if I had a shitload of money I could still buy my way out. If I can make the money legally, great. But if not, guess where I’m going to have to go looking again?

He chuckles. “Vicious cycle. Vicious motherfucking cycle.”

I try to lift his spirits. So, what do you miss most about home? I ask.

The first thing Nizam thinks of? His family.

“I’d like to thank my siblings for their support, both emotionally and financially when they could. But most of all, I’d like to thank them for taking care of the guy who used to take me for morning walks and see the birds when I was a child. Abah suffered a diabetic stroke, and he’s had a few heart attacks lately.

“I also miss my son and longtime soulmate. Oh, and cooking food!”

Hopefully you get out soon Nizam. IRL wishes you the best.

More from Real People

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …

‘I quiet-quit, upskilled, and tripled my salary,’ shares M’sian engineer

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that loyalty without leverage leads nowhere in the corporate world.After years of …

‘I did everything right, and it still wasn’t enough’ shares M’sian graduate

This story is about a Malaysian graduate navigating big dreams in a job market where a degree no longer guarantees …