[This story is retold by Suzanne Ling, the Co-founder and Storyteller of PichaEats, a social enterprise that serves catering food cooked by refugee chefs from around the world.]

Hi! I’m Suzanne, one of the co-founders behind PichaEats.

How PichaEats works is that we do food delivery, mainly for groups, Chinese New Year, 5 pax and above Christmas parties, weddings, buffet catering and meal boxes.

As a business, we ensure all the food is up to hygiene standards and quality, and we also train our refugees culinarily, to make sure that all of them stand strong as chefs.

We help people see them as not just victims, not just refugees, but as bona fide chefs that bring delicious food to the table.

It’s been 4 years since, and we are still fulltime in PichaEats, and we are still surviving. And throughout this journey, I realized I had learnt three lessons.

1. Find joy in what we do

Find joy in the things that we do, because we can either be bitter — or better.

All through my life, my plan for my path in life has always been: Have a degree in psychology, get a master’s in clinical psychology, get a PhD and become a doctor.

Actually, I wanted to be a doctor, but I didn’t have money to go to med school. So I did a detour – my plan was to do a degree, masters, and still become a doctor but for mental health.

When Picha started, my role became a marketing person. So from a psychology background to marketing and sales, oh my gosh – I hated it so much.

It’s not just that I was doing a thing that I didn’t like. I was also a bit bitter. I said to myself, “Eh, why am I selling food? Where is my Masters?” That’s my original goal.

After all, I got into this accidentally. When we started Picha, I was in my final sem in uni, and I started selling food to my friends, and then we tried it out for real. I have never ever wanted to start a business, and there I was, in the middle of one.

But at the same time… I really loved the purpose that we had, and I really loved the chefs that we worked with. So, there were a lot of emotions going into the business.

I loved Picha, but I hated my work. You see where I’m coming from?

Every time my CEO (Kim, the guitarist) would ask me, “Where’s the marketing strategy?” I also ask myself the same question, “Where is the marketing strategy?”

I was so lost and confused.

Every day I would mope around the office with thoughts like:

“I’m so miserable.”

“Where are the sales?”

“I just want to play with kids…”

“Why would they make me do this?”

I also was given the task of apologizing to our customers whenever we screwed up. Because according to my co-founders, I have a face that is the hardest to scold.

My job description is the Storyteller, but back then I was known as the Sorryteller.

When we screwed something up, I’d stand there and say things like, “I’m so sorry!” “Today the food was late, so sorry!” “Is everything ok? Sorry!”

One time I was scolded on the phone that I cried. (I don’t usually cry that easily, but that day ah, wah. I don’t know why people are like that.)

As much as I loved my business, I still questioned myself:

“Why am I doing this? I could have been doing my masters. I could have been in a hospital, listening to people’s problems.”

I know being a clinical psychologist is not an easy job, but that was what I wanted to be.

Then one day, I told myself: I can continue to be bitter, or I can change my mindset and start to enjoy what I had to do anyway.

Either I quit and really leave Picha, or change my mindset and learn to love what I do.

One random morning driving to work in the car, I had a shift in mindset.

“Aiyoh, angry also need to do, not angry also need to do, happy also need to do, not happy also need to do – why so unhappy, be happy lah.”

Just a simple shift of mindset, but it changed everything. Now when Kim asks me where is the marketing strategy, I’m like “Okay! Let’s think.”

Because no matter where we work or what we do, it always comes with something that you don’t like.

Are you going to keep looking for something to do that makes you happy, or are you going to find joy in the things you hate?

2. The clock is ticking, and we don’t have forever to live.

I learnt this lesson when I was 19.

I was doing A-levels, and I had a high school friend who finished a little earlier than me. We were close friends, and at night we’d always go to the pasar malam together.

When she finished her A-levels, she went to Pulau Tioman to do a turtle rescue program. And then — very suddenly — she drowned.

[image courtesy of ingrid wong]

I called that friend and asked, “Did you miss out a word? Did her grandma pass away?” And she said, “No, she passed away.”

We were 19. That was a huge slam in my face that yes, I am young and I am just doing A-levels. Life is just starting, but we can go anytime.

Because we were close friends, and I knew a lot of things that she wanted to do. She has always wanted to finish her degree and go to Nepal, and work as an English teacher.

But at that time, because she was waiting for that to happen, there wasn’t much going on, so she went on that island trip, and then she passed away suddenly.

And that hit me so much — this whole realization that we don’t have forever to live – and it really made me think about what I wanted out of life.

And if I am – like my friend — to go tomorrow, can I proudly say that I live a life that I am happy about? Can I proudly say that I have lived a life where I think, “I can go now”?

Yes, I wanted to work with kids. But why wait until I graduate? Why can’t I do something now, as simple as teaching the refugee kids near my house?

From that day onwards, I lived every single day keeping this mantra in mind: “If I am going to die tomorrow, is today a good day?” On the day I die, will there anything that I have done on this Earth that can continue along when I am no longer around?

Sounds very cliché, but that really changed my perspective towards life.

Right now, if I’m going to die tomorrow, I will be at peace with myself. I think I will be okay.

There is a quote from the book Tuesdays with Morrie: “Everybody knows they are going to die, but nobody really believes it.”

If we did believe in it, we would have done a lot of things differently. So, are you living the life that you want to live?

Lesson number 3: We can make a change. Life isn’t just about “me”

If all of us have the ability to choose what to eat and what not to eat, why can’t we do something within our capability to help others who don’t have a meal to eat?

I’m really not saying this in a way to make people feel guilty — it’s just a realization that the world is so big, with so many people out there.

My question is this: Is there something that we can do to help other people progress as we progress in life?

There are so many things we are chasing for, better technology, more innovation. But in chasing for it are we looking at the community with no access to it?

Are we bringing them forward with us, or are we leaving them behind?

When I ask that, I’m not talking about becoming Mother Teresa or starting PichaEats or dedicating your whole life to it.

It’s really about all the decisions we make on a day-to-day basis. And to illustrate this, let me tell you the story of the story of one of our chefs, Zaza.

The story of Zaza, our first PichaEats chef

Zaza is one of our chefs from Syria. In our 2nd month, he joined us as one of the pioneer chefs. His wife and son, Rania and Tai, come from Raqqa in Syria.

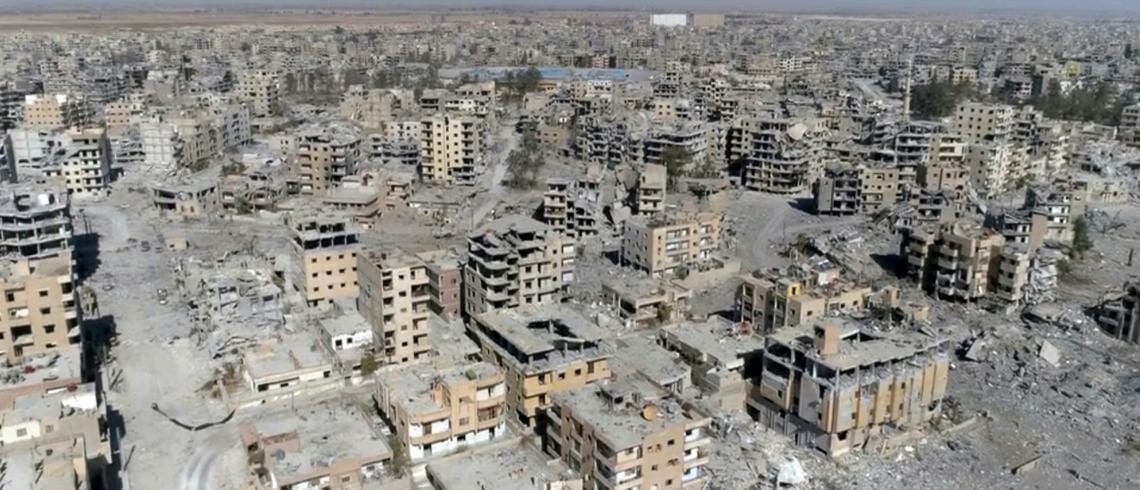

Raqqa was the HQ for Isis for many, many years. And at the time, everyone was attacking Raqqa. The US, Russia, the Syrian government – everyone was attacking it, because they wanted to drive the terrorists out.

[If you Google Raqqa, you will see photos of a totally destroyed city. Image via TRT World.]

[If you Google Raqqa, you will see photos of a totally destroyed city. Image via TRT World.]

One day, as Rania was bringing newborn baby Tai to the clinic to get a vaccination, an explosion happened nearby. Thankfully, it didn’t hit them — but the impact was so strong that it threw Tai out of her arms.

Rania quickly picked her son and ran back home. They didn’t get the vaccination that day. Which is a good thing – because:

A few days later, she found out that a lot of kids who got the vaccination actually fell very ill or passed away.

The vaccination had been contaminated.

You see, when you Google “contaminated vaccination in a disaster area”, it’s not a new thing — The agents who process your visa, they want to make money out of it.

They tell you that when you come to Malaysia, the Muslims here will welcome you, they will take care of you.

Then they get all your money, and when you come here, there’s nothing waiting for you. A lot of cases are like that. So when the Syrian refugees came here, they struggled a lot.

When we found them, it was because the United Nations told us they are really good chefs.

So we went to find them, and we found out they are very good chefs, and we started working together.

And we formed a very good working relationship with one particular chef, Zaza, because he truly had a very good heart.

He is the kind of person who, every time he has an order, he will cook extra food for the cleaners, for the runners. Every runner that picks up food for them will confirm get one box of food. And he is famous for that.

He will always pour out so much love to all of us; he would always tell us, “When the war in Syria stops, the three of you should come back with me to visit.”

Or he will say things like, “Oh you have guests coming over? I will cook the best because I wanna make you all proud.”

He is that kind of person, and he will always give his ideas to grow the business, because he knows that when the business grows, more refugee shares get to be on board.

And after being with Picha for a year, life really changed for him.

One day, he bought a cup of Starbucks and sent a photo to us. He’s like, “Hey, I bought Starbucks.” They could never ever afford Starbucks, and now — it was all these little things that made them truly very happy.

But unfortunately, life is always very funny, and weird, and unpredictable.

In February 2017, Zaza fell very sick. At first we thought it was anemia, because his blood iron was very low, so we gave him iron tablets. But by the end of February he suddenly got so weak that he couldn’t breathe.

We had to send him into the emergency ward. If you didn’t know, foreigners cannot actually get seen to unless they get a local Malaysian to guarantee that they will pay for them.

So, as he was almost about to faint, he was sitting outside the ICU on the road waiting for me to arrive to sign so that they will take him in.

I got a call at 11pm, and I rushed to the hospital. I saw him sitting by the road, took him in, and we went straight to the red zone, the critical zone. They took his pulse and said his blood pressure is low, blood count is low — everything was low.

A few days later, they told us that they suspected he had cancer. And that was when everything just went a very unexpected turn.

He was hospitalized. They did a lot of checks on him, took his bone marrow, and they did a lot of tests. And eventually they told us it was bone cancer.

But before we even got a confirmation of what it was, he passed away, very quickly, in May.

It was super sudden. None of us were expecting it, because the doctor two weeks ago told us he’s going to get discharged.

I remember that day very clearly.

We were at the hospital at 2pm because we got a text that he was very weak. We sat there, and a lot of us, with different religions all of us just started praying.

It was a strange scene — different religions praying different prayers. I was just like, “Please don’t go, please come back.”

At about 5pm he just — left. His organs had just shut off, and he just left, very suddenly.

It was one of the most painful moments we had in Picha.

All three of us began to question ourselves. We asked each other: “Why did this happen to him?”

This guy, Zaza, used to be a stranger to us. His death now affected us so much because we took him in, we took him in as a family.

Should we continue to do this? It’s so painful, do we still want to do it?

We doubted ourselves, but it was what Rania told me that kept us going

But after going through that, one thing that really helped me to keep going was what happened a week later, when we went to check on his wife, Rania.

Rania told us something that really impacted me a lot.

We asked her, “Are you ok? Is everything ok?”

And she replied: “Knowing that I’m with Picha, Zaza wouldn’t be worried about me even though he’s not around.” That was her answer.

When Rania said this, it was a very sure confirmation — we are doing this not just to support them financially, but also because it’s become something much more.

PichaEats became a support group for them; a friend to them in Malaysia when they don’t have anybody. And it’s really changing how people view the refugee community — people see that they have such a big heart.

And on top of that, what’s really amazing is what we witnessed two weeks before Zaza passed away, when the doctor said he’s gonna get discharged.

I went to the hospital in Ampang to see him, and he was doing quite good that day, two weeks before.

Out of the blue, he asked Rania to write down menus for us.

He said to his wife, “Ramadan is coming, make sure that we have a good Ramadan menu.” So, while sitting on the hospital bed, he was already curating the menu for Picha for Ramadan.

And I’m like, “But dude, you’re sick!” But he was someone with such a big heart. And he went on and he said, “The puasa (fasting) time is gonna come. ”

He said when he gets discharged, he wants to cook chicken Mandi, and give it out for free at the mosque to Malaysians, because that’s how he wanted to give back to Malaysia for having him.

And in my head, again I’m like, “Dude! What’s up with you?”

But of course I said, “Ya we’ll do it. When you come out, we’ll do it together.”

Then he said he wants to do this under Picha’s name, not Zaza’s name. He wanted to give out food for free, with his own money, as Picha. That’s what an amazing man he is.

I think from this whole short one year with Zaza, one thing that we learnt a lot is that he showed us how he could make a change, just by being him. By doing what he does best, which is through food.

And because he has been doing that, it has impacted so many of us, hopefully, many of you today, to hear his story, and to know that a simple act like this can make a huge impact.

Which brings me to my most important point…

How can you be you and make a change?

And what I mean by that is, how can you be you? Who are you?

Are you a singer, are you a video creator, are you working in a corporate office?

What is your strength? How can you use that to make a change?

And you’ll be surprised when you start thinking that way, a lot of things are possible.

For example if you are an accountant, you hate working with kids, it’s ok! Be an accountant – offer maybe an NGO who can’t hire an accountant and help them with accounting.

If you are good at marketing, there are actually a lot of mentors who reach out to us and help us in marketing so that we market the food better then the family gets the income.

So it’s really seeing what your strength is and offering your strength to people to make a change.

Today, remember this anywhere you go: How can you be you and make a change? No matter where you are in life, you can always make a change, somewhere, wherever you are.

To read how Suzanne started PichaEats with her two uni friends, read: We Were Three Uni Students Who Became Accidental Food Entrepreneurs. This is Our Story.

You might also like

More from Real Mental Health

“I Was Scared of Waking Up in Handcuffs,” shares Depressed M’sian on Repealed Law

In 2023, Malaysia repealed Section 309, a colonial-era law that made suicide attempts a crime. The change marked a shift …

‘Everyone Saw A Successful Student While I Was Crumbling,’ Shares 22 Year Old Student

This is a story of a 22 year old woman who shared her story as a Straight A’s student as …

5 Harmful Mental Health Myths Malaysians Still Believe

Let’s break down five of the most common myths Malaysians still believe, and why it’s time to let them go.