Disclaimer: In Real Life is a platform for everyday people to share their experiences and voices. All articles are personal stories and do not necessarily echo the sentiments of In Real Life.

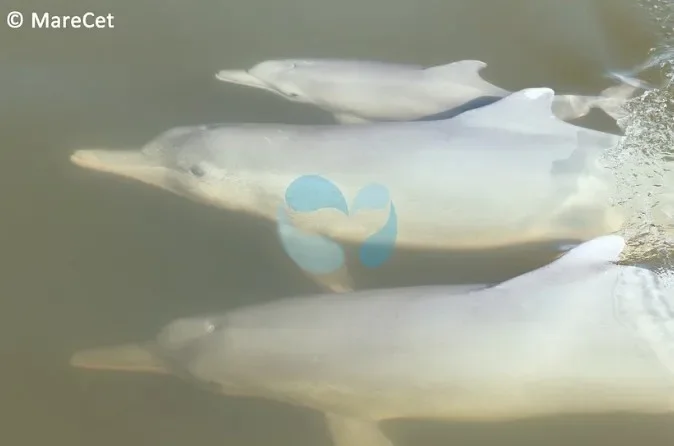

IRL spoke to the wonderful people at MareCet to find out what it’s really like to be a dolphin conservationist in Malaysia.

Did you know that dolphins can be sighted in Malaysia’s coastal waters? Not only that, but they actually call our tropical waters home?

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin is native to the shallow coastal waters of Malaysia and Southeast Asia. Image via MareCet/FB

According to Jeba, marine conservationist at MareCet, the species of dolphins that live in our waters include the Indo-Pacific dolphin, the dugong, and the Irrawaddy dolphin.

MareCet is the first and only non-profit NGO in Malaysia that is dedicated to the research and conservation of dolphins, whales, and other marine mammals.

What it’s like to be a dolphin conservationist in Malaysia

The Marecet team spends hours at sea, scanning the horizon with binoculars, taking photos of dolphins, and identifying them by their dorsal fins’ unique markings. Image via MareCet/FB

Being a dolphin conservationist might sound like a dream job, like being a zookeeper or park ranger. You might imagine it involves swimming with dolphins and spending days in the sun, surrounded by nature. But the reality, according to Jeba, is far more challenging.

“When I applied, it sounded like a very fun and easy job. You see dolphins, count them, key it into a spreadsheet, and your job is done,” shared Jeba.

The truth is far from this idealized image. Spotting dolphins is no simple task.

A dolphin sighting occurs on average once or twice every field survey trip. Image via MareCet/FB

“Most people think, oh, they jump out of the water, so it’s gonna be easy to spot them. But in reality, you’re always scanning the horizon, waiting hours for a fin to appear,” he explained.

It’s not uncommon to go eight hours under the blazing sun without seeing a single dolphin.

On clearer days, spotting dolphins is easier, but even then, the team often faces false alarms. Strong waves can look like dolphin movements, and rainy conditions reduce visibility, making their task more difficult.

Yet, even after hours of empty sea, when they do spot dolphins, every effort spent becomes completely worthwhile.

“The carcass was smelly and rotting”

A decomposed beached whale on the coast of Kedah, Malaysia. Image via MareCet/FBA

Every so often (several times a year), the team responds to stranding incidents around Peninsular Malaysia, such as Johor and Kedah, where stranded cetacean or dugong carcasses are reported.

One of the most challenging yet essential aspects of dolphin conservation is examining marine mammal carcasses. Since the animal is so elusive, carcasses provide easier access to researchers to study their diet or age, as opposed to wild, free-living animals in the sea.

“The first one I ever saw in the field was a beached dugong in Johor. With permission from the authorities, we took samples like teeth, bones, and skin, then we buried the animal on the beach. It was about 8 hours of hard work, but I was so excited and happy to be part of it,” recalled Jeba.

Examining the carcass allows researchers to understand the dolphin’s diet, life history, and potential causes of death, among other things. Image via MareCet/FB

Examining a marine mammal carcass is like an episode of CSI

“My first experience of a dolphin carcass was unforgettable. I was able to touch and feel the dolphin in real life, see what it looks like on the inside.”

“The most interesting organ is the melon – it’s an organ in the forehead of the dolphin that it uses for echolocation, communication, and finding food,” Jeba shared enthusiastically.

Dolphins have rows of sharp teeth which they use to grip their prey. Image via MareCet/FB

Sometimes, the MareCet team dissects carcasses that have been stored in the laboratory freezer for several months or years. “It was like a sausage that they put in the fridge and had to defrost. It smelled like salted fish that had gone bad,” Jeba described. The work can feel like an episode of CSI, Jeba says, once the team starts dissecting the dolphin.

“The hard part is cutting through the thick blubber, muscles and meat,” explained Jeba. “It’s like slicing a very thick piece of beef. The whole carcass smells so disgusting that some people would vomit, and the smell sticks on you until you properly wash.”

Cetacean skulls on display during an event in a national school, as part of MareCet’s outreach and education efforts. Image via MareCet/FB

Some of these collected samples and remains then make it into MareCet’s events and exhibitions, as a means of teaching and educating people.

People are often fascinated by the cetacean skulls and stomach content samples that they put on display.

Fun facts about the Indo-Pacific Bottlenose dolphin & Irrawaddy dolphin

The Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin’s territory range is from Madagascar to Australia, with India, Malaysia, and Indonesia in between. So yes, they do live in Malaysian waters.

They sometimes rub themselves over sponges, like the way cats rub themselves on human legs. It’s theorized they do this to clean themselves or treat skin infections as the sponges have antibacterial properties.

The Irrawaddy dolphin’s territory range is from Myanmar to Sumatra, Borneo and Thailand. Known for herding fish into a general area for hunting, they can even drive fish towards fishers. A pod of dolphins that agrees to work alongside the fisherman will entrap a school of fish in a semicircle, guiding them towards the boat. In return, the dolphins are rewarded with some of the fishers’ bycatch.

Garbage collectors for trash

“There are days when one wonders whether we are at sea to research cetaceans or be its garbage collectors.” Image via MareCet/FB

- Sea-borne trash is a huge problem for Malaysia’s marine wildlife. The trash builds up into floating islands, in which the poor animals get stuck in and cannot escape.

- “When we are out at sea on surveys, we are often juxtaposed with beautiful sceneries, when suddenly everything comes to a screeching halt when we encounter dolphins swimming through a sea of trash,” shared Dhivya Nair who is another MareCet team member.

The MareCet team conducts a few beach cleanups in a year, and each time they collect anything from 10 – 50 huge bags of trash. Image via MareCet/FB

Currently, Malaysia is No.8 in the world for the masses of mismanaged plastic inputs from land to sea. It was estimated that in 2010 alone, a whopping 4.8–12.7 million metric tons of plastic entered our oceans.

According to Jeba, the quantity varies depending on the season and the direction of the wind, which blows the trash from other countries to our shores. Of course, the rubbish that we see does not only consist of trash from other countries but also includes trash from our country as well.

Marine debris can easily get snagged on to a dolphin’s body, retarding its movements, and can also create wounds in its skin, leading to higher rates of diseases and infection, which can lead to eventual death. Image via MareCet/FB

There are also ‘ghost nets’ – nets which have been ripped away from their original setting, lost at sea during bad weather conditions (including falling overboard from the vessel), unused and partially torn nets that are not discarded properly, which then get stuck on dolphin heads, tails, fins, or anywhere on their body.

“Our team is constantly fishing trash out of the sea, on every single survey,” shares Dhivya. “We’ve rescued turtles stuck in plastic bags, diapers, slippers, clothes, and many other things that shouldn’t even be out there.”

The future of dolphin conservation

A MareCet volunteer speaking to a local fisherman, asking him questions about his experiences in sighting dolphins and his fishing activities. Image via MareCet/FB

MareCet aims to bring awareness to the Malaysian public, especially schoolchildren, decision-makers, and anyone living by the sea.

To this end, they conduct day-trip excursions, their Sea, Science and Schools Programme, Virtual Dolphin Tours, and even provide marine mammal stranding response workshops.

Their biggest and most ambitious undertaking has to be their Langkawi Dolphin Research Project, which has been ongoing since 2010.

They carry out research mainly on five species of marine mammals, which are the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise, Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, Irrawaddy dolphin, Dugongs and Bryde’s whale.

All dolphins are in trouble, some species even more so. According to this 2023 study, 1 in 4 species of cetaceans around the world are endangered. For example, the dugong populations have plummeted to alarming numbers—only about 100-200 left in the wild.

If you’re interested in donating to MareCet or contributing to their efforts, you can visit their website.

What do you think of this story?

Submit your opinion to ym.efillaerni@olleh and you may be featured on In Real Life Malaysia.

Also read: Why I Left My Comfortable Office Job in Kuala Lumpur to Work on an Island

Why I Left My Comfortable Office Job in Kuala Lumpur to Work on an Island

More from Real People

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …

‘I quiet-quit, upskilled, and tripled my salary,’ shares M’sian engineer

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that loyalty without leverage leads nowhere in the corporate world.After years of …

‘I did everything right, and it still wasn’t enough’ shares M’sian graduate

This story is about a Malaysian graduate navigating big dreams in a job market where a degree no longer guarantees …