Disclaimer: In Real Life is a platform for everyday people to share their experiences and voices. All articles are personal stories and do not necessarily echo In Real Life’s sentiments.

In recent news, a French historian called out University Putra Malaysia for allegedly using the wrong photo of a Jong in their published paper on maritime history.

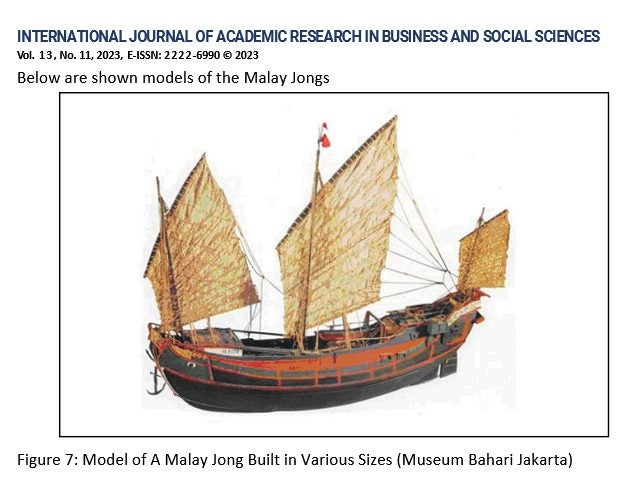

Basically, in November 2023, two academics from UPM, Rozita Che Rodi and Hashim Musa, published an article called: ‘The Jongs and The Galleys: Traditional Ships of The Past Malay Maritime Civilization’ in the International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences.

The French historian, a chap named Serge Jardin, pointed out in a Facebook post, “Shame shame shame! The photo does not show a Malay Jong but a Foochow Pole Junk from China.”

He further added, “International Journal of Academic Research, where is the peer-review?“

In response, UPM released an official statement, saying that the article did go through a process of blind peer review and was published in a refereed journal. They added that they take the accusations levelled against the university seriously, and that this issue should be discussed further in academic circles.

Jardin countered in a follow-up NST article that the journal itself, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, is a pay-to-publish, Open Access journal from Pakistan. The publisher, HRMARS, is listed as a predatory publisher on Beall’s list, a widely used reference for academics to identify exploitative publishers.

He added that it’s even been blacklisted by UKM (University Kebangsaan Malaysia) as a predatory journal, remarking it as “tidak diiktiraf” (“not recognised”).

” ‘Tidak diiktiraf’ (not recognised) by UKM but good enough for UPM?” he argued.

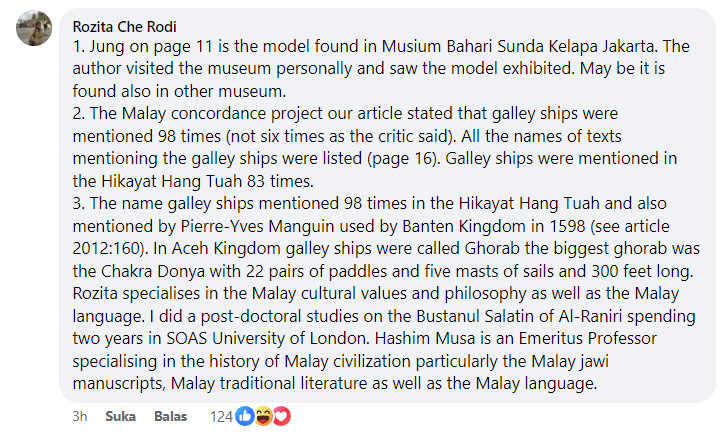

Rozita Che Rodi defends herself from Serge Jardin

In a response comment posted on Jardin’s Facebook post, one of the researchers, Rozita Che Rodi, clarified her process:

According to Rozita Che Rodi, the picture in question was sourced from the Musium Bahari Sunda Kelapa, in Jakarta, and the author visited the museum personally to review the model.

She also refuted his separate claims made in his Facebook post about how galley ships did not exist in Malaya until the Portuguese arrived, citing local sources such as the Hikayat Hang Tuah and Banten Kingdom.

Rozita specialises in Malay cultural values and philosophy as well as the Malay language. Her post-doc studies in SOAS University of London were about the Bustanul Salatin of Al-Raniri.

Hashim Musa is an Emeritus Professor specialising in the history of Malay civilization, in particular Malay Jawi manuscripts, Malay traditional literature, and the Malay language.

Now, before we all take out our pitchforks, let’s give the good people at UPM the benefit of the doubt. After all, Malay Jongs did originate from the Majapahit empire (in what is now modern-day Indonesia), but are often confused with Chinese Junks, which are similar but not the same.

What is the difference between a Malay Jong and Chinese Junk?

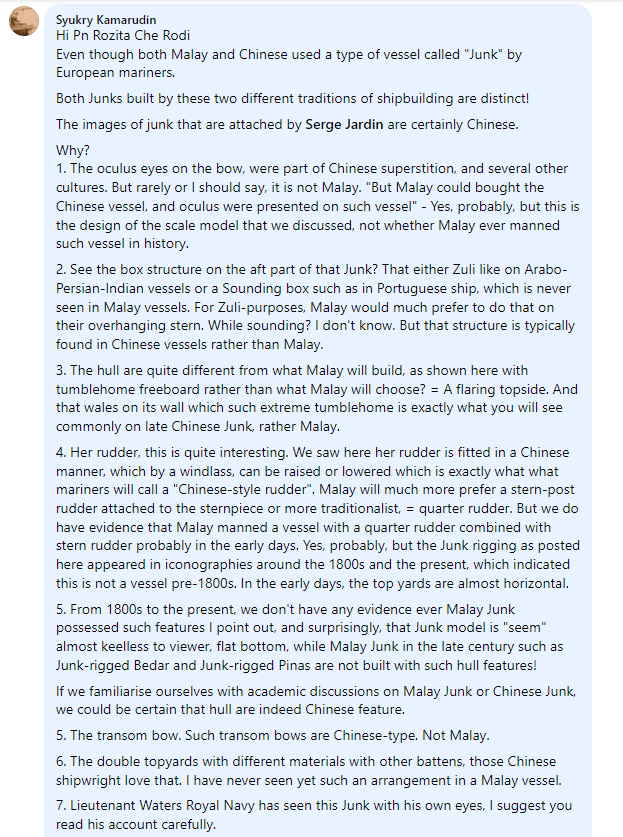

An independent researcher, Syukri Kamarudin, pointed out in another Facebook comment on the visual differences between the Malay Jong and the Chinese Junk, saying that the two traditions of shipbuilding are distinct.

He cited various features of the Jong used in the picture, such as the oculus eye on the bow, box structure, flat-bottomed hull, transom bow, double topyards, and so on, which defined it as a Chinese Junk.

“If we familiarise ourselves with academic discussions on Malay Jong or Chinese Junk, we could be certain that this type of hull is indeed a Chinese feature,” he said.

Kamarudin added that the Junk that the researcher saw was probably a copied-scale model or loan, mentioning that this same ship model is also exhibited in the NNM collection originally loaned from Oliver-Bellasis collection.

Here is his comment in full:

Aside from the independent researcher’s opinion, there are in fact many types of maritime ships that sailed the seas before the turn of the 19th century.

The actual origin of the design of such ships is contested by scholars. It is said that the Sumatrans, Sundanese and Javanese built their own ships, called Kapal Nusantara. (Nusantara refers to the entire archipelago of Indonesia and Malaysia, not just Peninsular Malaysia, during the Majapahit empire.)

According to various historical accounts, some Majapahit outposts across Majapahit-era Peninsular Malaysia allegedly loaned some Jongs from the Chinese empire, and they may have made some modifications to the Jongs to make them look more localised. In these accounts, Chinese Jong were made for long distance sailing, whereas Nusantara ships are more for hopping from island to island.

By Jong! Is it all a mistranslation?

Another interpretation of why this has become a huge debate is because of the drift in meaning of the word “Jong”.

According to The Vanishing Jong: Insular Southeast Asian Fleets in Trade and War, after the disappearance of jongs in the 17th century, the meaning of “junk”, which until then was used as a transcription of the word “jong” in Javanese and Malay, changed its meaning to exclusively refer to the Chinese ship (chuán).

This means that after the 18th century, the word Jong has become synonymous with the Chinese ship called the junk, even if its real origins could be traced back to the Majapahit Javanese two centuries earlier!

Who is right, Jardin or UPM?

Let us know in the comments!

Submit your story to ym.efillaerni@olleh and you may be featured on In Real Life Malaysia.

Read also: 4 Hari Merdeka Facts You May Not Know About

4 Hari Merdeka Facts Like “The Bangle Of Independence” You May Not Know About

More from Real People

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …

‘I quiet-quit, upskilled, and tripled my salary,’ shares M’sian engineer

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that loyalty without leverage leads nowhere in the corporate world.After years of …

‘I did everything right, and it still wasn’t enough’ shares M’sian graduate

This story is about a Malaysian graduate navigating big dreams in a job market where a degree no longer guarantees …