![Growing Up With My Tai-po and Her Secret Chinese Recipes in In Real Life [Family Photo Of My Great Grandparents And Their Brood. Grandpa (The Tallest Guy From Right) And Mom (Girl In White From Right).]](https://inreallife.my/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/52d084c6-e8c5-4448-8ce9-617e6b6bdc19.jpg)

[Family photo of my great grandparents and their brood. Grandpa (the tallest guy from right) and mom (girl in white from right).]

In Kuching, there is a street called Jalan Khoo Hun Yeang. It’s made up of a few shop lots selling electrical goods, food, and souvenirs for tourists.

Once, back in the 50s and 60s, this place was bustling and thriving with business. How do I know? My mom used to live atop one of the shops as a child.

Mom lived there with her 4 younger siblings, her parents, and her grandparents. All 3 generations of the Wong family co-existed under one roof.

I recall mom reminiscing about her youth and how she loved her grandmother’s (I call her Tai-Po) cooking. She loved it so much she kept a journal about all the delicious food Tai-Po used to cook.

[Jalan Khoo Hun Yeang. Image via St. Joe Form 5 (1976) on Blogspot]

What Life Was Like In the 60s

Tai-Po’s other children lived nearby and would visit often. During festive seasons, the whole family would squeeze into the rooms on the 2nd floor of the shop.

Great-grandpa (Tai-Kung) would roll up the only floor mattress and turn their bedroom into a makeshift dining room.

The adults would gather around a big round table and enjoy their meal, while the grandchildren would eat at their own little table down the corridor.

We had many annual festivals: Chinese New Year, Dragon Boat Festival, Hungry Ghost Festival, and the Mid Autumn Festival.

We’d celebrate them with feasts. The tables would groan with all the numerous dishes prepared.

But first, we’d light the joss sticks and candles, and food would be offered to the ancestors and deities before anyone was allowed to eat.

Mom, her siblings, and cousins would eagerly wait for the joss sticks to burn out before they could dig in.

Making Tang Yuan for Mid Autumn Festival

Tang Yuan, the round glutinous dumplings, is a dish that is served during the Mid-Autumn Festival.

On the festival day, Tai Po would bring out her precious millstone to grind the glutinous rice. She would hold the stone handle and turn the stone round and round, making a low grinding sound.

Come evening, all the water would have been squeezed out by the weight of the mill.

[Grandmother grinding the rice into flour. Image by Chen L. Zheng]

The flour would become a dough, ready to be made into tang yuan.

Then, she and her daughter-in-laws and a few grandchildren would all sit around a table and shape the dough into marble-sized balls.

There would be 3 types of balls: the white and pink balls would be cooked in sweetened ginger soup, while the other type would be filled up with chopped Chinese sausage and preserved vegetables (Tong Choi) to be cooked in a savory soup.

The little ones loved the sweet version while the adults enjoyed the savory ones.

[Tang Yuan in the shape of a pig. Image via Unsplash]

[Tang Yuan in the shape of a pig. Image via Unsplash]

The Morning Market At Gambier Street, Kuching

Every morning would be a market morning for Tai-Po. She would weave her way through the crowded market to buy daily necessities such as poultry, vegetables, and fruits.

The wet market was at Gambier street, overlooking the Sarawak River and the Astana. I had the privilege to visit the market a few times as a child before it was torn down.

Occasionally, she would buy some satay sticks to reward my mom or any of her grandchildren who accompanied her.

Back home, Tai-Po and her daughter-in-laws would begin to prepare for the day’s dishes.

Sometimes, they would make fish balls from scratch. First, the fish would be cleaned and the flesh scraped off. The remaining fish head, skin, and bones would be steamed and given to their cat.

The fish meat would then be pounded in a pestle with salt and pepper until it was elastic enough to form into balls for cooking in soups or fried into fish cakes.

Every day, the family would be served with soup, three kinds of vegetable dishes, a meat dish, and an egg or tofu dish.

Occasionally, Tai-Po would treat the family to her very own version of Sarawak Laksa. It was vermicelli (bee hoon) cooked in curry. I ate this once and it reminded me of Penang Laksa.

Roasting Sarawak Coffee

[Coffee beans on a round wok. Image via Nohat]

A monthly event, which mom and my aunts and uncles eagerly awaited for would be the roasting of the coffee beans for the family’s daily coffee intake.

Coffee beans had to be roasted every month and Tai-Po would fry the beans in a big wok until all the rooms were filled with the aroma of coffee.

When the coffee beans turned black, they would be quickly taken off the fire. Butter and sugar were then added to give the beans more flavor.

Once the beans cooled, Tai-Po would bring them to a Hainanese coffee shop for the ‘towkay’ (owner of the shop) to grind the beans for a small fee.

As a refrigerator was not a usual household item back then, the remaining tinned butter had to be consumed within days.

So for the next 2 or 3 days after the roasting of the coffee beans, the Wong family would enjoy bread and butter for breakfast.

The grandchildren would rejoice at the change from the usual breakfast of local cakes.

Tai-Po would be sure to lovingly serve Tai-Kung bread without the crust (great-grandpa had very few teeth left by then), spread with thick butter, and sprinkled with sugar.

Kuih Nyonya Was Also A Big Part Of Our Tradition

[Assorted kuih-muih. Image via Malay Mail]

On other days, the freshly brewed coffee would go with an assortment of cakes that Tai-Po bought from the market before the break of dawn.

The local cakes included the Ang Koo Kuih (Mung Bean Paste Cake), Huat Keuh (Steamed Palm Sugar Muffins), Pak Tong Kow (Steamed Sweetened Rice Cakes). Exotic Nyonya kuih such as kuih seri muka, the rainbow-colored kuih lapis, and kuih kochi were also a breakfast norm.

And sometimes, the grandchildren got to enjoy deep-fried turnip cakes and chai kuihs.

The most memorable ones to be eaten with the homemade coffee were the Ham Chin Peng (Cinnamon doughnuts) or Yau Char Kwai (Chinese Crullers).

These two dunked into freshly brewed coffee were to die for….mmm-mmmm! It was and still is a family favorite for us all.

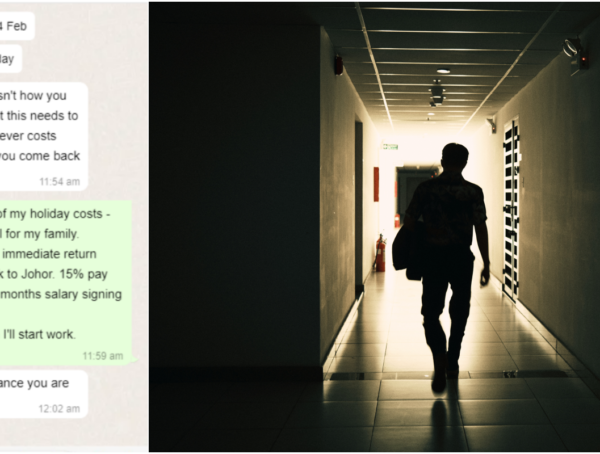

Making Mandarin Peel Orange Duck for Chinese New Year

[The Chan Pei Arb. Image via JessKitchenLab]

Among the dishes for Chinese New Year would be sweet ginger and soy sauce chicken, steamed crabs, deep-fried prawn fritters, and abalone soup.

But the prized dish would be the ‘Chan Pei Arb’ (Mandarin Peel Orange Duck) and ‘Chap Chye’ (vegetarian Stir-Fried Glass Noodles).

The Chap Chye was my personal favorite, and the only dish that I managed to master.

The Chan Pei Arb was and still is the family pride, with the recipe handed down from generation to generation. It may not look much, but the taste would blow even Gorden Ramsey away.

My aunts told me that Tai-Po brought this recipe all the way from China and had perfected the art of cooking this dish. Apparently, not many Malaysians know about this dish.

Days before the celebration, mom and her cousins would peel off the skin of mandarin oranges and dry them under the hot sun.

After that, the dried orange peels would be used to enhance the flavor of the duck meat, which would then be fried in a big wok (with a few secret ingredients) before being transferred to a slow pot.

Making ‘Ghost Money’ for Hungry Ghost Festival

[Paper folded into ‘ghost money’. Image via Half a pound of treacle on Blogspot]

On the 15th day of the 7th month, the Hungry Ghost Festival would be celebrated.

Before the day arrived, Tai-Po would buy gold, silver, and multi-coloured hues of ‘ghost money’.

Mom and her gang would race against the clock to see who could make the most money origami — folding and pleating the paper into silver and golden ingots.

On Festival day, there would be a lavish lunchtime feast offering. At night, the ‘ghost money’ would be burnt by the street side.

Meanwhile, goodies such as bananas, lotus roots, steamed sponge cakes, peanuts in shells and peanut sweets would be offered to other wandering lost souls.

Making Dumplings for Dragon Boat Festival

The Dragon Boat Festival has its origins in the story of a Chinese official who threw himself into the river in protest — after the emperor refused to listen to his pleas about the common peoples’ plight.

It was said that if people all around China threw glutinous rice dumplings into the river, the fishes would eat them instead of his body.

But Tai-Po saw no reason to throw the dumplings into the Sarawak River — it would be such a waste. So she made the dumplings for her family instead.

To prepare the dumplings, about a week before the festival, Tai-Po would bring my mom and aunts to the nearby bamboo groves to harvest the leaves.

The leaves would be soaked in water for several days, then they would meticulously separate the ordinary rice grains from the glutinous ones. It was a tedious task that no one liked.

[Glutinous dumplings. Image via Phoenix4BN]

Two types of dumplings were made: One had no meat filling and was eaten dipped in sugar.

The other one had fragrant minced pork fried with dried mushrooms, preserved sugared winter melon cubes, grounded coriander seeds, roasted chestnuts, pepper and soya sauce.

Tai-Po and the ladies would wrap both types of dumplings with bamboo leaves like a pyramid, before fastening them with reed string and boiling them.

Nowadays, we use steamers, but back then, the Wong family couldn’t afford one, so the dumplings would be steamed in big empty tins instead.

After an hour of boiling, Tai-Po would take the dumplings out and air-dry them by the kitchen window.

The Importance Of Eating Together

Even though Tai-Po passed away many years ago, her legacy lives on.

To this day, my aunts and uncles still remember vividly the meals that she cooked for them and the times they spent together as a great big family.

Many of her recipes have been passed down to the current generation.

I hope that they will continue to be passed on, along with stories of Tai-Po’s cooking skills whenever her descendants gather together for a family feast.

For more stories like this, read: 5 Things Our Grandparents Did That We Don’t Do Anymore and I Challenged Myself to Cook Every Day Because I’m A 29-Year-Old Who Only Knows How To Toast Bread.

You might also like

More from Real People

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …

‘I quiet-quit, upskilled, and tripled my salary,’ shares M’sian engineer

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that loyalty without leverage leads nowhere in the corporate world.After years of …

‘I did everything right, and it still wasn’t enough’ shares M’sian graduate

This story is about a Malaysian graduate navigating big dreams in a job market where a degree no longer guarantees …