Disclaimer: In Real Life is a platform for everyday people to share their experiences and voices. All articles are personal stories and do not necessarily echo In Real Life’s sentiments.

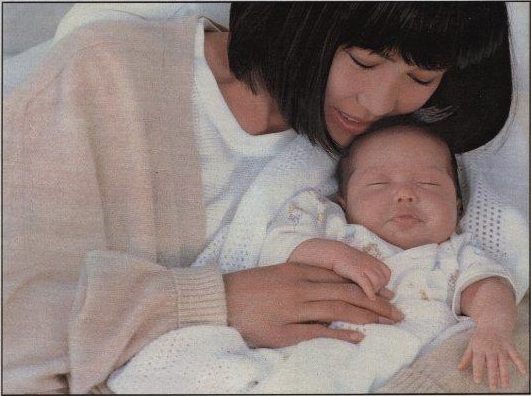

This is a childhood memory of my mother’s:

She’s about eight years old. Her father has made hibiscus syrup from blooms he gathered in his own garden. The drink is brightly coloured and sweet; everyone loves it. Get your tumblers, her father says, turning from the stove. My mother, excited, grabs hers and is first in line, holding it out. Everyone holds out their tumbler.

One by one, my grandfather fills them all up from the big pot, but he doesn’t fill my mother’s. Even though she’s the youngest child there, he skips hers. He’s filled nearly everyone else’s, even the adults’, when my grandmother says: The poor child has been waiting for so long! Can’t you fill hers too? Then my grandfather finally ladles some syrup into my mother’s tumbler.

My mother remembers being confused, although this isn’t an isolated incident: she already knows her father loves her less than he loves the others, or even, perhaps, that he does not love her at all. She remembers her cheeks burning, her arm aching from holding her tumbler out for so long. But she’s thirsty and she knows she mustn’t talk back, so she quietly drinks her syrup.

All of this may be misremembered. All of this may be only my mother’s version of events. Nevertheless, she has spent her life wondering why her father loved her less. Soon there will be no one left to ask, and then she herself will be gone, but she has passed the wondering on to me.

Sometimes, my friends ask me: You still care about Malaysia, don’t you?

It’s clear you do, because if you didn’t, you wouldn’t get so angry about what happens here, you wouldn’t get so sad. You haven’t lived here in nearly thirty years, but you still pay so much attention, it’s like you’re here. You talk about what’s happening in Malaysia more than anywhere else.

I think about this question a lot. I am suspicious of my own fixation sometimes, wary of writing about Malaysia just for attention, just for the hungry gaze of the West. No one can escape that gaze, certainly no one who writes in English. But what the West likes best are stories that include it in some way, and most of what I have to say about Malaysia does not include the West. Most of it is a story about me and Malaysia, and it goes like this:

A very long time ago, when I was a child, I lived in a place that resembled the Good Mother in fairytales. Soft and warm, perpetually beaming, smelling of sunshine and sago gula melaka and hot oil. The love of a child for her mother is its own kind of love, and perhaps it shouldn’t even be called love: it is dependence, it is trust, and sometimes we confuse these things with love. Does a goldfish love its bowl? Does a Christmas pig love the farmer? The feeling you have for the only life you know is not a feeling you choose freely. Whatever that feeling was, I felt it. I felt it even though I saw that this Good Mother loved some of us less than the others.

When I was very small, the signs were subtle. Some of us were in the framed family photos on the walls; others weren’t. Some of us would be rewarded for good behaviour; others wouldn’t. Some of us would be chosen for things, appointed to special posts, presented with prizes and medals, and we could all see that none of this matched up exactly with who did what best.

These inconsistencies bothered me in the way they bother many small children: they didn’t add up, they didn’t make sense, they offended my rigid sense of Justice. But all you know really is all you know, when you are small. It must be the same everywhere, I said to myself. This is how the justice of adults works. This is what Good Mothers are like.

People tried to warn me: you know she doesn’t really love you. Be careful. Don’t trust her. Make your own plans. To all this, I nodded impatiently. I know, I know, I said. But part of me always thought: how bad could it really be? We’re still her children, all of us.

Vintage pampers advertisement

“If you don’t like it here, go back.”

The older I grew, the clearer the signs — no, more than signs, because sometimes this Good Mother took it upon herself to put some of us in our places explicitly. I picked you out of the gutter, she would say. You should be grateful. This isn’t really your place. You don’t belong here, but I let you stay because I’m Good like that. Don’t you get too big for your boots. If you don’t like it here, go back.

People’s warnings, too, grew more explicit: you know the Good Mother is never going to change her mind, don’t you? It is written this way in her book, in black and white. The book cannot be changed. The book is her script, and she is never going to deviate from it.

Still, it was all we knew. We went on with our lives. The days were long and sunlit. We had each other. We tried not to think too much about the fact that the Good Mother loved some of us more than she loved others. We tried not to let it come between us.

You go on like this, when you grow up in a home like that, and then, one day, you’re grown up. And you go to the Good Mother and you say: the time has come for me to seek my fortune. Can I have my share of the inheritance?

Beyond the allegory, this moment happens in a phone booth.

You’ve scoured your parents’ house for coins to make this phone call. You say, these are my SPM results. You say, I scored all these A’s, including an A1 in French. The person at the other end of the line, who works at the French Embassy, says, “Sorry, we only give scholarships to Malaysians through the Malaysian government.” You fling your remaining coins into the monsoon drain and walk home in tears.

Some months afterwards, after many of your mother’s newspaper clippings, your own phone calls, and dozens of interviews, you find a different way to escape. Years later, you meet the people who got those scholarships to France. They’re all very nice. They’re all kids of the type the Good Mother loved back. It’s not like she lied about it. She told you from the beginning that she loved them more. You just tried not to believe it. That’s not their fault; it’s your fault.

I’ve told the story of this moment in the phone booth before, in almost these exact words. I’ve posted it on social media, I’ve summarized it on comment threads. Now when I tell it here again, some people will say, Oh god, not that story again, she really is obsessed with that story. And: what’s her problem? She’s fine now, isn’t she? She’s successful, she lives a great life in France, why does she have to keep dwelling on the past as though she really suffered, as though she grew up in some terrible refugee camp in a war-torn country?

These people are right in some ways: I am obsessed. I often think of that phone booth moment. And I am mostly fine, fine enough on the surface, anyway, yet I can’t get over my old resentments. Blame it on my temperament. Blame it on my good memory. Things stay vivid for me, often too vivid. Whatever the reasons, I can’t exorcise the Good Mother. Children of abusive parents can choose to cut off contact: I could choose that, I could stop reading the news, I could delete my social media accounts, I could, when my parents are dead, stop going back to visit. But no matter how abusive the parent, the child cannot choose their memories. Oh, to be able even to dial them down.

Vintage formula advertisement

We, the ones who weren’t loved back, do not all feel this way.

Some of us left, some of us stayed. Some of those who left say: Time to move on with our lives! Some of those who stayed say: You know you’re not helping anyone by talking about your past. And you don’t live here, you don’t see all the moments when the Good Mother is really not so bad.

Some of them even say: the Good Mother is not the injustice. The Good Mother is not the unfair rules written in the book, or even the book itself. The Good Mother is not her minions, either; she is more than all these things. All those things are terrible, but the Good Mother is Good, and we will always love her because she’s our Mother. You’re failing to see who she really is.

But who is the Good Mother, then, I ask them, and where is she, and why wasn’t she there for me when I needed her to see me and stand up for me?

At these moments, it’s as though these people and I are not speaking the same language: they answer questions, but not the questions I’m asking. You don’t see all the ways we are here for each other, they tell me, the strong bonds we’ve formed to make up for everything else. When you don’t live here you forget the complexity of it, the textures, the smell of the rain and the secrets the city whispers to those who are patient.

It’s not that I don’t believe them, but sometimes I wonder: how much of this is what they have to believe to protect themselves? I think of the stories children tell themselves about abusive parents. Remember that time he bought us a whole roast chicken with the last few ringgit of his pay, and he didn’t even eat any of it himself? Remember the way she’d climb into bed with us and hug us close all night after beating us till we bled? These memories aren’t invented, but the brain offers them up: Here, take this one. You need it.

I think my brain used to do that too. And then I left, and the truth is, I did try to move on with my life. I do move on with it, day after day. But then I have weeks like last week: weeks when I see friends thanking God for privileges the Good Mother denies others. That the Good Mother herself believes God smiles upon her neglect and abuse: it burns my stomach. An abusive parent who acknowledges her own whims and caprices, who pleads, my anger just gets the better of me sometimes, what to do, I’m like this, is one thing.

But an abusive parent who declares this is what God wants is another thing altogether. And an abusive parent who has convinced her favoured children that their special treatment comes from God, that she is only the intermediary — this is a poison still strong enough to derail my week.

Vaithu erichal, we call this lasting stomach burn in Tamil.

Last week I asked a friend who also left: What’s wrong with me, why can’t I get over this? Why can’t I be happy for other people? So what if the system that was unkind to me favours them? Isn’t this petty of me?

But my friend is like me: No, she said, no, it never goes away. Your vaithu erichal, I feel it too.

“mother and child,” gustav klimt

Weeks like last week, the Good Mother and her children announce their plans to sit around the family dinner table discussing a racial slur my father can’t talk about without flinching.

My father is not a man of delicate sensibilities; nor he is gentle and refined in his own speech. He grew up at a time when people said what they wanted to say. Someone said something to you, you laughed, you said something worse back. Everyone laughed. No one knew which laughter was sincere and which laughter was a thin veil over the vaithu erichal. If your stomach burned, you took the burn home and nursed it in private.

This word they wish to discuss is the word that made my indelicate, foul-mouthed father’s own stomach burn, and my mother’s, and my brothers’, and mine. I think of those who are going to discuss the word dispassionately, adjudicate on our right to choose our own labels, and I realise that vaithu erichal is not only cumulative within a single life, but passed from one generation to the next.

Weeks like that, I look at the scraps they throw us — Look, we included an Indian for you! Look, here’s someone who looks like you on the cover of a book — and I see why their efforts are so clumsy: it is because they don’t know us. They don’t know what we wear at weddings, what we eat at home, what we call our prayers, what our men feel when they see a policeman approach. When we tell them, if we can get them to listen, they are genuinely surprised.

Even as they express their delight at having learnt something new and their gratitude to us for teaching them, we are privately thinking: where have you been all our lives? Why is what you know about us a minuscule fraction of what we know about you?

Bollywood is more familiar to them than the culture of the people they have lived with for centuries. They have had the lack of curiosity of the privileged, which can result only in the charity of the privileged: but we did this for you, what do you mean this does not represent you, why are you never happy, why is it never good enough? You should be grateful. They say it more kindly than the Good Mother herself does, but in the end, they are her minions. That’s not their fault, either. They hardly have a choice. It is nearly impossible to escape the service of the Good Mother once she has chosen you.

“You still care, don’t you? You still love her, don’t you?”

Weeks like that, the question my friends ask me is more present than ever: You still care, don’t you? I’ll never know how to answer it. It is a dangerous question to ask the grown child of an abusive parent. You still love her, don’t you? You clearly think about her all the time.

That part is true. I think about her all the time. She takes up a lot of space in my head. She occupies it permanently, the rent-free tenant I can never evict. There is no other tenant like this. There never will be. But is that because I love her most, or because no one else has ever betrayed me quite as deeply? After all, I’ve never needed any other Good Mother the way I needed her when I was a young person finding my way in the world, trying to figure out where I belonged. I was never a small child at the knee of any other Good Mother, holding out my tumbler till my arm hurt, waiting for the syrup she was ladling into everyone’s tumbler but mine.

The face of the first Good Mother in your life is the face that will forever fill your head, and when you see it in your memories you’re also seeing your younger, more vulnerable self. This is not true of the places you inhabit later in life; those places may be kind or unkind to you, hospitable or inhospitable, but the relationship you have with the place in which you grow up will never be replicated. Those other places influence your life, even control aspects of it, but they do not decide who you will be.

Only the Good Mother is a part of you, running in your blood, resisting the words you try to put to her. She is more than the sum of the parts you can describe: the soft touch of her skin, the smell of her clothes when she turns from the stove, smiling, ladle in hand. You never stop imagining what your life might have been if she’d loved you the way she loved — and still loves — others.

The very fact that you can imagine it makes you soften towards her, because it is impossible to separate the ache for what might have been from the pain of what was. It all melts into one hazy, elusive vision. It’s the Ghost of the Possible Past, and it will haunt you for the rest of your days. But is this caring? Is this love or its opposite? Does it have a name, and will you ever discover it?

Preeta Samarasan is a Malaysian author writing in English whose first novel, Evening Is the Whole Day, won the Hopwood Novel Award, was a finalist for the Commonwealth Writers Prize 2009, and was on the longlist for the Orange Prize for Fiction. You can read more of her stories here.

For more stories like this, read: My Husband’s Parents Didn’t Invite Me For Chinese New Year For 10 Years Because I Was Indian and I’ve Been a Foreigner in Malaysia for a Decade — Here’s Why I’m Leaving.

You might also like

More from Real People

‘A RM100 fee cost a company 5 years of revenue’ shares M’sian

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that bureaucracy can be defeated simply by not arguing with it.A billing …

‘I quiet-quit, upskilled, and tripled my salary,’ shares M’sian engineer

This story is about a Malaysian who learned that loyalty without leverage leads nowhere in the corporate world.After years of …

‘I did everything right, and it still wasn’t enough’ shares M’sian graduate

This story is about a Malaysian graduate navigating big dreams in a job market where a degree no longer guarantees …