Life can sometimes be unpredictable, just like how nobody foresaw the results of the 14th General Elections. In this new Malaysia, I sit down with a friend of mine called Nasha*. We’re in a noisy café, and we’re both sporting Panda eyes because we (like so many other Malaysians) have been staying up late into the wee hours of the morning after polling day, reading the news.

Nasha gets up for a few seconds to shake the hands of the couple at the table next to ours. They’re her friends and we’re all here for an arts festival featuring crafts, poetry performances and forums. Nasha sits back down and she asks the first question “So, what angle are we looking at?”

Nasha’s life hasn’t been easy. She’s been living with depression since she was in secondary school. “I never talked about it. There really wasn’t anyone to talk to about it either. In fact, I didn’t even know what I was experiencing. Information on depression was really limited back then.”

She says her depression doesn’t have a trigger, or at least none that she can pinpoint clearly. “My teachers and parents chalked it down to bad behavior whenever I missed school. I held it in and withstood all the symptoms and suicidal thoughts until it subsided. Yes, that’s how bad the depression got for me.

“In that environment, I made my way to Jogjakarta to study medicine in about 2002, after finishing my matriculation. My matriculation results weren’t good enough for me to study medicine locally. But I was fortunate to get this scholarship to study medicine in Jogja.

“Jogja was really good for me in the beginning. I mixed with the local Indonesian students way better than other Malaysians.”

So what happened to make her drop out of medical school?

“It wasn’t just one particular event. It was a lot of things happening at once. The University admins lost one of my assignment papers and I had to extend my studies to another semester. My boyfriend at the time broke up with me. I was completely broke.”

“I’ve had enough at that point and I just decided to stop studying. Eventually, I was bumming around from one friend’s home to another. This lasted for about a year and a half. In between, I would end up on the streets. During this time I hung out with a group of street buskers and performers. This gave me some security and I would stay in the group to protect myself from any trouble. Sleep was done sitting up while my buddies performed, or on someone’s lap, but only for an hour or two every night. Back then, I had youth on my side.” she jokes.

“Sometimes I would just put my head on a table at the roadside ‘waroeng’ and fall asleep. No pillows or blankets.

“Food in Jogja was cheap. You could get a plate of fried rice for Rp 2,000 (about RM0.70). Well, back then at least. Usually, the peeps in my busking group took turns paying for everyone’s food, from the day’s collections. I usually helped them by clapping along. I tried singing for a while, but I wasn’t that good. I think they paid me just to get me to stop,” she laughs.

“Meals weren’t regular. Sometimes I would eat just once a day.”

“I did do some translating and proofreading work when the opportunity came by. I felt so down at this point I didn’t even try and contact my family. Eventually, I was offered a well-paying office job, but had to work for under a false name. My visa had expired and my passport too by this point. I was a persona non grata.”

At this point there were so many questions in my head, but I decided to ask the most pressing one. How did she find her way home to Malaysia?

“Well, through the help of some friends, I managed to find a lawyer willing to take up my case. Not many lawyers want to take up persona non grata (individuals with no legal identity) cases. It’s messy and complicated, and they stand to lose their reputation too. Through my job I managed to raise about two thirds of the funds and some of my friends pitched in to make up the full amount.

“It took some time, but I eventually got my documents in order, and came back here. At the time I also had to settle the question of my scholarship, and I had to get a doctor’s letter confirming my depression for them not to harass me for repayments. ”

“I was living under a lot of paranoia. I didn’t think I could trust my family, which is why I kept interactions to a minimum. Though they did send someone to look for me. Now, our relationship is more cordial but it wasn’t like that for a long time. I think they tried to understand me, but they just didn’t get it. They were like ‘What’s so hard about medical school, just go back and we’ll pay for it.’

“I’m still trying to understand my own condition. I used to think it was seasonal and happened at the end of the year. I brought it up with the first psychiatrist but now I’m not so sure. I used to be under medication but now I cope without it. A support network of friends and my husband is enough to help me cope at this point. Also, because I don’t really trust our public mental health system (I went to school with some of them, so yeah) and I can’t afford private-lah,” She tells me.

Image credit: nasha

“My medical background helps me know where I need to do my research, and I feel we’re definitely making progress in terms of mental health. The first step is always to be open, and to know that you’re never alone.”

*Name changed to protect privacy

For more articles by Michelle read Coming out of the Closet: A Transgender Man’s Experience or My Life as An Indonesian Migrant Worker in Malaysia.

More from Real Mental Health

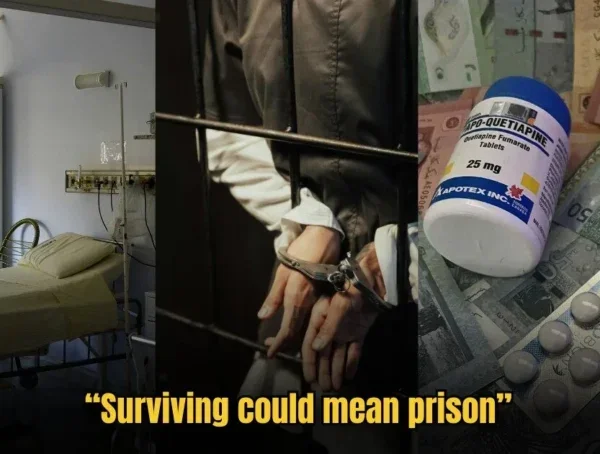

“I Was Scared of Waking Up in Handcuffs,” shares Depressed M’sian on Repealed Law

In 2023, Malaysia repealed Section 309, a colonial-era law that made suicide attempts a crime. The change marked a shift …

‘Everyone Saw A Successful Student While I Was Crumbling,’ Shares 22 Year Old Student

This is a story of a 22 year old woman who shared her story as a Straight A’s student as …

5 Harmful Mental Health Myths Malaysians Still Believe

Let’s break down five of the most common myths Malaysians still believe, and why it’s time to let them go.